Duke’s first Lone Star Western

.

On one level Riders of Destiny is just another John Wayne B-Western of the 1930s with little extra to recommend it. However, on another level it was quite a key moment. The great leap forward into stardom that Fox’s Raoul Walsh-directed epic The Big Trail had promised in 1930 turned out to be no leap at all. The huge-budget picture drove Fox to the edge of bankruptcy against the background of the Depression and Wayne found himself lucky to get work at all. The three pictures he made for Harry Cohn at Columbia were cheap junk in which he didn’t even top the billing. The six Warner Westerns he made 1932 – 33 were a lot better, and Wayne was paid $850 each for them, but once the Warners contract expired it was not renewed. Wayne was depressed and concerned. He married in June ‘33 and children were soon on the way.He needed work.

On one level Riders of Destiny is just another John Wayne B-Western of the 1930s with little extra to recommend it. However, on another level it was quite a key moment. The great leap forward into stardom that Fox’s Raoul Walsh-directed epic The Big Trail had promised in 1930 turned out to be no leap at all. The huge-budget picture drove Fox to the edge of bankruptcy against the background of the Depression and Wayne found himself lucky to get work at all. The three pictures he made for Harry Cohn at Columbia were cheap junk in which he didn’t even top the billing. The six Warner Westerns he made 1932 – 33 were a lot better, and Wayne was paid $850 each for them, but once the Warners contract expired it was not renewed. Wayne was depressed and concerned. He married in June ‘33 and children were soon on the way.He needed work.

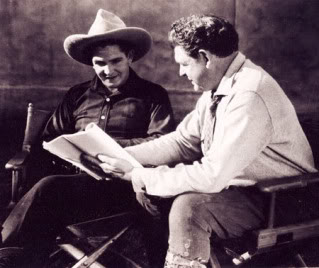

His friend the producer Paul Malvern (right, late in life) promoted a series of Westerns at Monogram. It was a long way down from Warners, or even Columbia. Poverty Row studios like this were where actors usually ended up, not where they made it big from. The sixteen pictures Wayne made there from mid-‘33 to mid-‘35 were known as the Lone Star Westerns and certainly they were very low-budget. But because they are in the public domain (you can find most on YouTube) they have remained amazingly current. Riders of Destiny was the very first.

His friend the producer Paul Malvern (right, late in life) promoted a series of Westerns at Monogram. It was a long way down from Warners, or even Columbia. Poverty Row studios like this were where actors usually ended up, not where they made it big from. The sixteen pictures Wayne made there from mid-‘33 to mid-‘35 were known as the Lone Star Westerns and certainly they were very low-budget. But because they are in the public domain (you can find most on YouTube) they have remained amazingly current. Riders of Destiny was the very first.

The director, as on many of the pictures, was Robert N Bradbury, whose son Bob Steele had been a pal of Duke’s since youth. Bradbury had an eye for good locations, liked flashy camera action, could churn out a picture on time and on budget, and would often bash out the vivid (sometimes almost lurid) scripts on a typewriter as well (average time taken, four hours).

.

.

RN Bradbury (right) with his son Bob Steele

.

His cameraman was the aptly-named Archie Stout, who had been working at Paramount on those talkie remakes of Zane Grey silents that Henry Hathaway was directing. Stout was an ornery cuss but he was greatly talented – as John Ford was to find later.

.

.

Archie Stout (great hat)

.

Malvern had a good eye for character actors who would work cheaply and was especially fond of George ‘Gabby’ Hayes, who often filled the comic/crusty old-timer role, though he was only in his mid-40s, and another pal of Duke’s, Yakima Canutt, who would take charge of the stunts – some of which were quite impressive – double for Wayne and also often play a henchman.

.

.

Gabby seems pleased that his daughter likes Duke

.

Another reason that this first Wayne Lone Star outing is famous is that he played the character Singin’ Sandy, “the most deadly gunman since Billy the Kid”, who sang a dirge-like song as he walked down the dusty street for the quick-draw showdown with the bad guy. Wayne couldn’t sing worth a damn. They dubbed him when he was serenading the gal or in the first reel as he rode his white horse Duke while strumming his guitar and crooning. The dubbed operatic singing was that of a rich and fruity baritone, a million miles away from Wayne’s normal voice. But in the showdown sequence Wayne had to sing himself, and it’s hilariously bad. The clip has gone viral and is very amusing watching.

.

.

Dubbed (fortunately)

.

The hired gun whom Singin’ Sandy shoots (only wounding him, naturally) is none other than Earl Dwire. I love the lugubrious Dwire, who appeared in numerous Lone Stars, but he was nearly always a kindly sheriff, banker or other worthy townsman. To see him as two-gun Slip Morgan, evil henchman decked out all in black, is a real treat.

.

.

Earl Dwire (center) is the hired gunfighter. That’s crooked town boss Forrest Taylor in the suit.

.

Bradbury (who wrote this one) was especially fond of the mistaken identity plot device, and anyone found kneeling over a body is assumed immediately by everyone else to be the killer. So Duke spends a lot of time in these movies with people shooting at him or trying to hang him. Of course in reality he is usually an under-cover government man, sent out West from Washington to thwart the nefarious schemes of the chief villain, always a man in a suit and usually with a thin mustache. This time it’s a certain Kincaid (Forrest Taylor) and he’s one of those crooked town bosses who wants the whole valley and is forcing ranchers to sell up cheap by cornering all the water rights. Taylor was already a veteran stage actor when he started appearing in silent movies but by the mid-30s he was on Poverty Row. He would later be the bad guy in Johnny Mack Brown oaters and was still going in TV Western shows in the 50s. He does well in Riders as a smoothie crook.

There was always a gal, of course, and this time it’s Cecilia Parker, Mickey Rooney’s older sister in those Andy Hardy pictures. Gabby is her dad. She and Sandy fall in lerve, obviously, and kiss in the last scene.

.

.

Duke on Duke

.

Al St John and Heinie Conklin play two comically inept henchmen. Quite amusing, I suppose.

There are couple of brutal horse falls, normal for the time but they still give me the creeps. Even Duke is tripped and the hero (or Yak anyway) unhorsed. In another stunt a horse plunges into a lake. I hate it.

Still, these pictures are energetic and fun. They rattle along. There are no subtleties to spoil the enjoyment of the juvenile audience and the characters often explain the simple plot to each other in the dialogue. It looks really quite reasonable for a $10,000-budget film.

If you want to explore mid-30s John Wayne Westerns, this would be a good place to start. You’ll get 53 minutes of amusement.

.

.