Wayne Morris good as hard-bitten gunfighter

A short time ago I reviewed a big color widescreen picture Allied Artists put out in 1958, Cole Younger, Gunfighter, directed by RG Springsteen. I said then that it was a remake of the studio’s earlier movie, The Desperado, starring Wayne Morris. Well, I’ve just watched The Desperado and I would say that Cole Younger, Gunfighter was indeed a remake: a very faithful one. OK, the gunfighter central character wasn’t Cole Younger in the original (he was named Sam Garrett), and the earlier one was in black & white, but scene for scene and dialogue for dialogue, the later picture was a re-creation of the first one. To the point where you could hardly credit Springsteen for directing the ’58 film at all; it was really the doing of the man who helmed the 1954 picture, Thomas Carr.

A short time ago I reviewed a big color widescreen picture Allied Artists put out in 1958, Cole Younger, Gunfighter, directed by RG Springsteen. I said then that it was a remake of the studio’s earlier movie, The Desperado, starring Wayne Morris. Well, I’ve just watched The Desperado and I would say that Cole Younger, Gunfighter was indeed a remake: a very faithful one. OK, the gunfighter central character wasn’t Cole Younger in the original (he was named Sam Garrett), and the earlier one was in black & white, but scene for scene and dialogue for dialogue, the later picture was a re-creation of the first one. To the point where you could hardly credit Springsteen for directing the ’58 film at all; it was really the doing of the man who helmed the 1954 picture, Thomas Carr.

Carr was one of those journeyman directors who put in his time churning out low-budget oaters and then did wagonloads of TV Westerns (187 episodes of 18 different series!) He’d actually started out as an actor in silent movies as far back as 1915, and aged 17 had been one of the railroad workers on John Ford’s The Iron Horse (but then, who wasn’t?) He started directing in 1945, one-hour Sunset Carson second features for Republic, and also worked on the studio’s serial Jesse James Rides Again with a pre-Lone Ranger Clayton Moore. Johnny Mack Brown, Jimmy Wakeley, Lash La Rue, James Ellison, Whip Wilson, if any screen cowboy needed a director who could turn them in on time and on budget, Tommy Carr was your man. Probably his biggest and best Westerns were two he directed at the very end of his career, The Tall Stranger with Joel McCrea in 1957 and Cast a Long Shadow with Audie Murphy in 1959. And he did a good job on The Desperado. Dan Stumpf said that Carr was “a soul consigned to toil for eternity in B-movies and cheap television, but he took his fate like a low-budget Sisyphus, moving his camera for maximum effect, turning out the best of Bill Eliott’s final westerns with a fluid camera and sure sense of pace,” which puts it rather well. Though myself I might have accorded Bill Elliott the full quota of Ls in his name. But that’s just me being picky.

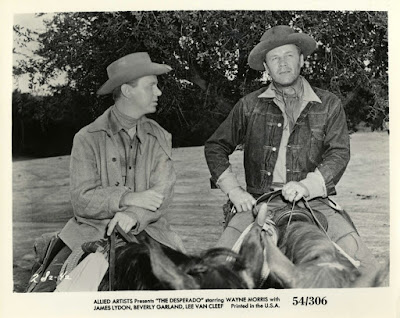

I was maybe slightly dismissive of Wayne Morris in a previous review, that of The Younger Brothers (when he really did play Cole), suggesting that he wasn’t really cut out for our noble genre. I am prejudiced, you see, against blond Western leads; they don’t cut it. Though they are OK as baddies. But actually I think he’s very good in The Desperado. Maybe it’s because he plays a baddy. Or at least that classic Western figure, the good badman. Cynical and ruthless, unshaven and looking haunted, he is convincing as a wandering gunman whom even the law steers well clear of. I must watch some more Morris oaters (I’ve ordered a couple) and give him more of a chance. Blond or not.

In some ways, though, as I said when writing about Cole Younger, Gunfighter, the gunfighter is not the central character/hero. That’s more the young man who meets up with him and becomes a killer himself. It was James Best in the ’58 version but the role was played in this picture by Jimmy Lydon, not really a Western specialist, though he did lead in his very first oater, Fox’s Tucson, in 1949. He had small parts in Death of a Gunfighter and Rage at Dawn. He appeared in only six Westerns movies altogether, though he did a fair number of Western TV shows. He’s not bad as Tom Cameron, the green kid who learns how to survive in the school of hard knocks.

The young man he thinks is his friend but who turns out to be a snake in the grass, Ray Novak, is played by Ray Barnes (Buck in The Wild Bunch and Charlie Pitts in Young Jesse James). His dad, the local lawman, is an old pal, Roy Barcroft. The part of the girl that both the lads love, Laurie (though she has eyes only for Tom), is taken by Beverly Garland, George Arliss’s sister, who achieved Western greatness as Marshal Rose Hood in the weirdly watchable Roger Corman picture Gunslinger, one of those gal-with-a-gun Westerns that Hollywood liked.

Ray (far left) and Tom (center left) are beaten by thuggish state police capatin and his equally thuggish sergeant

The Desperado starts with an over-the-top intro text which sententiously sets the story in Reconstruction Texas. Reconstruction was all bad in Westerns; it had no saving graces at all. That was because Hollywood movies at this time were exclusively white affairs and the idea that Reconstruction might have been good for some black Texans was either ignored or indeed thought to be positively seditious. I quote it here, though it is far too long (fortunately the 1958 version cut it down):

This one is set in John’s City, HQ of the wicked state police, which is headed up by brutal Cap’n Thornton and his equally thuggish sergeant/sidekick. Good news: the captain is played by Nestor Paiva and the sergeant by John Dierkes, reliable Western bad-guys both. A young man (it is Tom) hangs an effigy of Governor Davis from a tree, paints BLUEBELLIES GO HOME on the front of their office and then throws dynamite at the building and at the saloon, unofficial headquarters of the loathsome captain, who is irked.

Cap’n Thornton beats the two boys up, trying to get them to admit that they blew up the HQ and referred to the inmates slightingly as Bluebellies. In the end, the two young men can take no more and fight back, departing with the two policemen out cold on the floor. Serves ‘em right.

Now they have to go on the run, to that notorious haunt of owlhoots, the Big Bend country. There they come across famed gunfighter Sam Garrett (Morris), who has a price of $10,000 on his head, and Ray wants to turn the outlaw in for the reward. “He’s Sam Garrett!” he tells Tom. “He’s killed more than twenty men! He’ll kill that many more if somebody doesn’t stop him. Stopping a man like that isn’t just a job for the law. It’s a job for every man who wants to live in peace – every man who wants law and order to come back to Texas.” Tom replies caustically, “And for every man who wants to save his hide and collect $10,000! Stop making righteous speeches, Ray!”

Well, the upshot is that Ray skulks back to John’s City, vowing to get even with both Tom and Garrett, while the two new friends travel on. Sam rapidly becomes Tom’s mentor, teaching him to shoot and also how to be cynical and ruthless. Useful lessons, you will agree. For example, “Only a fool,” he says, “sticks his neck out for somebody else. Don’t get in the habit of it.” Sage advice. But we know for a fact that in the last reel Sam will stick his neck out to help Tom, and sure enough…

Now they meet Lee Van Cleef. It’s during one of the few location shots (most is done in the studio). He’s the one who plays two twin brothers (a useful budgetary economy) Paul and Buck Clayton. It was Myron Healey in the remake. Paul has had to shoot his horse and he casts covetous eyes on Tom’s mount, which, indeed, he tries to steal, but Tom has now learned a lightning-fast draw and deadly accuracy, so it’s RIP, Paul.

Now Tom decides to go back home and face the music. But once there Laurie tells him that his pa is dead. The state police tried to beat Tom’s whereabouts out of him and he succumbed. So we get the classic bit where Tom straps back on his guns. He’s going to get revenge. “Don’t go!” Laurie pleads. “Not if you love me!” You know how dames do. But we know, don’t we, dear fellow Westernistas, that a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do. Of course he gotta. So a showdown looms.

There’s quite a lot of plot to come yet, though. We’ll get a (low-budget) cattle drive and a scene in Abilene, which nestles neatly in those well-known Abilene mountains (all the town shots are done up at the Iverson Ranch). The marshal of Abilene is not Wild Bill, nor even Bear River Tom Smith, but a certain Jim Langley, one of those lawmen who believes that discretion is the better part of valor, by quite a long way. He’s played (rather well) by Dabbs Greer, who made his film debut as an extra in Fox’s Jesse James back in 1939, which was filmed mainly in Pineville. “They were paying $5 a day a day to local people for being extras. That was really good money in those days, more money than we had seen in a long time.” He once said, rather sadly-hopefully, I think, “Every character actor, in their own little sphere, is the lead.”

Tom will have to face Paul Clayton’s brother Buck, who is even faster on the draw than Paul was. So Jimmy Lydon got to shoot Lee Van Cleef twice in the same picture, which has to be unusual. And there will be a climactic trial scene in which the truth will out.

Silvermine Productions made it, a company which made a lot of Westerns, especially for Monogram, and it was distributed by Allied Artists Pictures, whereas AA both produced and distributed the remake itself in 1958.

Both pictures were scripted by Daniel Mainwaring from a novel by Clifton Adams. Mainwaring, often credited as Geoffrey Homes, as here, was responsible for quite a few not-bad sagebrush sagas (though also a few ho-hum ones).

The DP on The Desperado was Joe Novak; perhaps that’s where the bad guy character’s name came from. You might spot Franklyn Farnum as a courtroom deputy, and you’ll certainly recognize the ugly mug of William Fawcett as the bar tender.

Good stuff, really, and especially notable for Morris’s performance – as good as Frank Lovejoy’s in the remake. I don’t know (yet) if it was Morris’s best Western, but it could have been.

5 Responses

Perhaps I really oughta wait for you to catch up with Morris's other Monogram/Allied Artists westerns before confirming that this IS Wayne Morris's best western IMO, Jeff! Actually though I really quite like his other westerns in the series too but, whereas the others are decidedly 'B' pictures, "THE DESPERADO" stands apart. This is partly its feature-length and partly its darker, more adult treatment.

I also rather like the series of crime thrillers Wayne Morris made in Britain during the mid-1950s.

Right. Discussion to be continued, then!

Jeff

They say history is written by the winners, but in Hollywood the confederacy seems to have written history for many years. In the novel the Oxbow Incident, the leader of the lynch mob was a former confederate officer, but in the movie version they added dialogue that he was only pretending to be an ex-confederate and he never lived in the south until after the war.

Richard

In the humorous book 1066 AND ALL THAT, an irreverent survey of English history, the English Civil War was summed up as being between the Parliamentarians, who were Right but Repulsive, and the Cavaliers, who were Wrong but Wromantic. Hollywood Westerns seem to have adopted a similar approach to the American Civil War. Slavery was airbrushed out of oaters almost entirely and when African-Americans appeared at all it was only as faithful family retainers. As far as post-war Reconstruction goes, I don't know of a single Western movie that showed it as a good thing or even a nuanced thing; it was all bad.

Jeff

The appreciation of the importance of the Black African-american people in the West is relatively recent but Hollywood is still far behind the reality – maybe a subject for a next Jeff,s article!? -. There is a lovely little museum in Denver showcasing this history, The Black American West Museum and Heritage Center. It has been estimated that 25% of the cowboys of the 1865-1890s were black – they were very good in rodeos – and several regiments of the US Army too, including the famous 9th and 10th Cavalry. I have seen in 2019 at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, a statue dedicated to the Corporal Greaves, one of the 23 Buffalo Soldiers to receive the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars. A fascinating history which should inspire much more the script writers. JM