Hawks’s Western masterwork

Red River was the only Western in which Howard Hawks matched the artistry of John Ford. It is a mighty film, epic in nature and in the nation-building, quasi-historical vein of some of the greats of the genre, but with traits of dark post-war angst too. One thinks of Ford while watching it not only because Hawks elicited a stunning performance from John Wayne but also because of the epic grandeur of the movie, the noble themes and the fact that each shot is framed as a work of art.

Ford does seem to have had some input to Red River. Tag Gallagher, in his book John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press, 1984), suggests that Ford assisted Hawks on the set and made numerous editing suggestions, including the use of a narrator. It may have been so. Certainly Ford wrote to Hawks asking him to “take care of my boy Duke”. Hawks did say that he often thought of Ford when shooting, particularly in a burial scene when ominous clouds started to gather. Hawks later told Ford, “Hey, I’ve got one almost as good as you can do – you better go and see it.”

It made Wayne a major star. The Big Trail (1930) for Raoul Walsh and Stagecoach (1939) for Ford had both turned out to be false starts as far as ‘A’ Westerns were concerned. After Stagecoach, Ford had used Duke in The Long Voyage Home and They Were Expendable, but not in a Western. When the director made his Wyatt Earp story My Darling Clementine at Fox after the war, he used Fonda, not Wayne. It was really Hawks who made John Wayne into the cowboy megastar he became.

Red River was filmed in the fall of 1946, i.e. well before Ford’s cavalry trilogy, though it did not come out until September 1948 for various reasons. Hawks wanted endless editing and there was also an absurd claim by Howard Hughes that the picture was similar to The Outlaw (it was nothing like it; for one thing, Red River was good). If anything, the plot was a Western Mutiny on the Bounty, as co-writer Borden Chase (Charles Schnee was the other writer) admitted. In any case, the picture wasn’t released until after John Ford’s Fort Apache.

A reader, StereoSteve, wrote me: “The first version of Red River I saw, as a 10 yr-old, was an old 35mm copy of what is now called the ‘pre-release’ version, with Walter Brennan’s voice-over narration in place of the diary entries occasionally superimposed on the screen. I always considered that version superior. Apparently, the switch between the two is part of what held up the picture’s release – Hughes said Brennan’s narration infringed on The Outlaw’s copyright.”

Wayne must have hesitated to take the part of Thomas Dunson. To play a much older man (he was 39 then) losing his grip, with no female partner (Joanne Dru’s Tess was destined for Montgomery Clift as Garth) wasn’t an obvious step for him. But it was a great part and Wayne carried it off supremely well. After seeing Wayne’s performance in the film, John Ford is quoted as saying, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act” – which was a bit rich after Stagecoach, in which Wayne had pretty well outshone all the rest of the cast. Wayne’s portrayal of an older man probably convinced Ford to use Duke as the retiring officer in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon in 1949, a part he had slated for Charles Bickford, and Duke would do that part too with great skill.

Red River, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande, some of the best Westerns ever made, were all released in the space of three years (1948 – 50) and Wayne was superb in all of them.

He loved Red River, and continued to wear Dunson’s belt with its Red River D as the buckle in later Westerns. In a 1974 interview, Hawks said that he originally offered the role of Thomas Dunson to Gary Cooper but Coop declined it because he didn’t believe the ruthless nature of Dunson’s character would have suited his screen image. Interesting idea, though.

Hawks seems to have borrowed a good number of other Ford stock company members as well as Wayne because Walter Brennan, Harry Carey Sr and Jr (this was the only film in which father and son both appeared, although they had no scenes together), Paul Fix, Hank Worden and others are all on the cattle drive.

Brennan as Wayne’s sidekick and crusty cook Groot and John Ireland as Cherry Valance, the leering gunman rival to Montgomery Clift’s Garth, are particularly good (amazingly, even Cary Grant was considered for Valance). Joanne Dru (soon to be Mrs Ireland and also to star in Yellow Ribbon for Ford, as well as Wagonmaster) is pretty but you get the impression that her part has been artificially grafted onto the story for some love interest. That sometimes happened with Hawks (and Ford too). There is a suggestion that Dru was second choice, when Margaret Sheridan became pregnant. As for Brennan, author Howard Hughes in his guide to Westerns Stagecoach to Tombstone says that “ex-stuntman” Brennan “was a friend of Hawks and his initial three day’s [sic] work was expanded to six weeks” but I’m not sure about that.

Eastern method actor Monty Clift (he couldn’t ride a horse and had to take lessons) in his movie debut is excellent as the adopted son of the Bligh-like Dunson who finally rebels, in a Fletcher Christian way, takes over the herd and sets Dunson adrift. Michael Coyne, in his book The Crowded Prairie, makes the point that his character is a prototype of all those angry young men and rebellious teenagers that were to populate movies all through the following decade. “Matt Garth was the spiritual progenitor of the youth-rebels of the 1950s.” He is small and sinewy, not at all like the beefy Wayne (how to make the final fistfight convincing was a real problem for Hawks, who evened the odds by having the gunman Cherry wound Dunson just before the fisticuffs), yet he conveys power and even a growing authority. Wayne and Brennan didn’t care for Clift, who was left-wing and a homosexual. In an interview with Life magazine, John Wayne described Clift as “an arrogant little bastard”. He would have preferred Burt Lancaster for the Clift part but Lancaster turned down the role to star in The Killers. Still, though they shunned Clift socially, Wayne and Brennan worked professionally enough with him.

Noah Beery Jr as decent cowhand Buster is fine (as he always was). And among the bit parts you can spot Glenn Strange the Great as a cowboy and Shelley Winters as a dance hall girl.

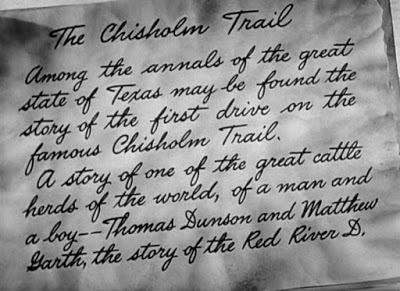

The story starts when Dunson is young, setting up his own cattle ‘empire’ and adopting a young boy, Matt (Mickey Kuhn), the only survivor of a wagon train attacked by Indians. Without missing a beat the film skips forward 14 years (it was 20 in Chase’s original story The Chisholm Trail) when Dunson, now the classic cattle baron, decides to drive cattle from Texas to sale in Missouri. Matt is now grown and has become Montgomery Clift. In The Encyclopedia of Westerns Herb Fagen says, “Wayne’s Dunson emerges as the prototype of rancher-hero, a man as tough as he is stubborn, a western trailblazer consumed by blinding ambition and a near-impossible task.”

So it becomes what Coyne calls “the archetypal Odyssey Western”. The drive makes its long and weary way through fine Western locations (Arizona, mostly) to the studio sound stages where they camp each night.

Roger Ebert reminds us that “when Peter Bogdanovich needed a movie to play as the final feature in the doomed small-town theater in The Last Picture Show he chose Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948). He selected the scene where John Wayne tells Montgomery Clift, “Take ’em to Missouri, Matt!” And then there is Hawks’ famous montage of weathered cowboy faces in closeup and exaltation, as they cry ‘Hee-yaw!’ and wave their hats in the air.”

The tension builds and builds towards the final reckoning that we know must come.

Hawks was perhaps attracted to the story because of the male triangle at its heart. Garry Wills, in his biography of Duke, John Wayne, The Politics of Celebrity (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1997), makes the point that all Hawks’s Westerns had this trio. In The Outlaw, Doc Holliday (Walter Huston) and Pat Garrett (Thomas Mitchell) were rivals for the affections of Billy the Kid (Jack Buetel). In Rio Bravo you have John Wayne as the sheriff, Dean Martin as the alcoholic deputy and Ricky Nelson as the pretty-boy gunman Colorado. In El Dorado, Robert Mitchum takes the drunk deputy part while James Caan becomes the younger man, Mississippi (though hardly a gunman in this case). The male trio is usually complemented and hovered over by a cranky old mother-hen figure: Walter Brennan in Red River and Rio Bravo, Arthur Hunnicutt in The Big Sky and El Dorado. In Red River, of course, you have Dunson, Matt and Cherry (Wayne, Clift, Ireland) with Brennan as the mother-hen.

You don’t have to have read much Freud to smile at the scene in which Cherry Valance and Matt Garth exchange guns and have a shooting match.

Cherry: That’s a good-looking gun you were about to use back there. Can I see it? (They swap guns) Maybe you’d like to see mine. (Cherry examines Matt’s pistol). Nice, awful nice. You know there are only two things more beautiful than a good gun. A Swiss watch or a woman from anywhere. You ever had a good Swiss watch?

Only the showdown at the end comes over as a compromise. It’s marvelous as Wayne walks, blazing with anger, through the cattle and disposes of the top gun with a dismissive shot. Here comes the clash with Clift!

But in no time at all, Dru, in a rather silly speech, has Dunson and Clift making up and it all peters out. Dunson has been so driven, so indomitable, that almost no ending would have worked, except perhaps his death. The same is true of Ford’s The Searchers, when Wayne’s film-long fury dissipates in a short scene and he takes Debbie ‘home’. He should really have died, as in the book. It is said that Hawks himself scripted Dru’s speech, in a fit of pique against John Ireland (Hawks was, it is alleged, a rival for the favors of Ms Dru). Clift’s character was to have shot Dunson fatally, then faced a showdown with the gunman played by Ireland. Dramatically, that was necessary as the two young guns had been locking horns, more or less playfully, throughout the story. But it was fudged. Roger Ebert said, “The final scene is the weakest in the film, and Borden Chase reportedly hated it, with good reason: two men act out a fierce psychological rivalry for two hours, only to cave in instantly to a female’s glib tongue-lashing.”

In a way, the male triangle resolves itself at the end, with Cherry out of the way, into a familial/generational one, with grandfather Brennan, father Wayne and son Clift. Garry Wills even talks about them as Laertes, Odysseus and Telemachus but I think we’re getting a bit hi-falutin’ here. It’s only a Western movie, after all. Hawks himself had no time for over-intellectualizing his films. He made straightforward pictures with a good story.

Red River is an unusually long film for the time (125 minutes) and Wayne thought it too long, but it never drags. Throughout, it is dusty and smells of cattle. It’s a huge picture with thousands of head of steers and a half-million dollar budget which grew to $3.2m. Scenes like the beeves going down the main street of ‘Abilene’ are still impressive today. See it on the big screen if possible.

The picture made the investment back, though. It was 1948’s third-highest grossing film at $4.15m US and went on to make $10m worldwide. Only Road to Rio and Easter Parade made more. Viewers loved the rouisng tale and post-war audiences must have responded to Dunson’s promise to “flood the nation with good beef for hungry people.”

The music, by Dimitri Tiomkin, who often worked with Hawks, is powerful and memorable. Western buffs will sing “My rifle, pony and me” to the theme tune, Settle Down, because they will be Rio Bravo fans – and Settle Down was later adapted by Tiomkin for use there. Not that other Hawks Westerns, Rio this or Rio that, were a patch on this great work.

The greatness of the film is also largely down to Russell Harlan because the black & white photography is simply stunning – not only the famous 360° shot at the start but throughout. Hawks had wanted the super-talented Gregg Toland, and Harlan had really been confined to B-Westerns previously (Hopalong Cassidy flicks and the like), but Hawks and Harlan worked outstandingly well together and made a visually great picture. There is apparently a colorized version, but I don’t particularly want to see it.

9000 cattle were used for the shoot with 70 trained riders. The stampede was filmed by fifteen cameras in ten days and several wranglers were injured doing it.

The importance of Red River as a Western can be judged by the number of times it is mentioned in reviews of other films and used as a comparison. It is a touchstone, as Stagecoach is.

It was nominated for two Academy Awards. Bosley Crowther in The New York Times wrote that the film “is on the way towards being one of the best cow-boy pictures ever made. And even despite a big let-down, which fortunately comes near the end, it stands sixteen hands above the level of routine horse opera these days.” Variety said it was “a masterful interpretation to a story of the early west and the opening of the Chisholm Trail”, adding, “The staging of physical conflict is deadly, equalling anything yet seen on the screen.” The Motion Picture Herald praised it as “a rousing tale rold with hard-bitten enthusiasm in the heroic tradition of those epics of the West which have brought credit to the screen and profits to the exhibitors since The Covered Wagon.”

Later critics have also praised it. Roger Ebert wrote, “Red River is one of the greatest of all Westerns when it stays with its central story about an older man and a younger one, and the first cattle drive down the Chisholm Trail.” He said, “Hawks is wonderful at setting moods. Notice the ominous atmosphere he brews on the night of the stampede–the silence, the restlessness of the cattle, the lowered voices. Notice Matt’s nervousness during a night of thick fog, when every shadow may be Tom, come to kill him. And the tension earlier, when Dunson holds a kangaroo court.” However, Ebert does temper his admiration when he adds, “It is only in its few scenes involving women that it goes wrong.”

But overall he admires the picture greatly. “The theme of Red River is from classical tragedy: the need of the son to slay the father, literally or symbolically, in order to clear the way for his own ascendancy. And the father’s desire to gain immortality through a child (the one moment with a woman that does work is when Dunson asks Tess to bear a son for him). The majesty of the cattle drive, and all of its expert details about ‘taking the point’ and keeping the cowhands fed and happy, is atmosphere surrounding these themes.”

Brian Garfield said, “The epic power of Red River is immense. It’s a classic Western.” He is certainly right.

It’s curious in a way that Hawks made it at all. It was his attempt, a risky one, to become an independent producer (he bought the rights to the story for his own Monterey Productions), but why choose a Western? He was much better known for slick, urbane movies with clever dialogue. But he did have some Western track (or trail) record. He had started as production manager and editor on 1920s silent Westerns for Paramount, been fired as director from Viva Villa! in 1934, had helmed the semi-Western Barbary Coast in 1935 and he had contributed to the dreadful The Outlaw earlier in the decade but was fired by Howard Hughes after two weeks. He was hardly a Western expert. But Red River made him one.

The picture was remade for TV in 1988 with James Arness as Dunson, Bruxe Boxleitner as Matt and Ray Walston as Groot. You might even argue, though this is a bit of a stretch, that CBS’s Rawhide had a Dunson-ish Gil Favor, a Matt-like Rowdy Yates and a crusty old Grootish Wishbone.

Hawks never again did anything as good, certainly not a Western anyway (you might like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes). His four later Westerns, The Big Sky (1952) with Kirk Douglas and those three commercial ‘bankers’ with Wayne, had nothing like the artistic merit or scope. Red River remains one of the best Westerns in the history of the genre, one of Wayne’s very greatest portrayals and it is unchallenged as the finest cattle-drive movie ever.

Pure gold.

13 Responses

It’s a giant in the genre! Not only did Wayne wear the belt buckle in later Westerns, but he also wore the bracelet or wrist band that was given to him in the picture in many of his subsequent films. The yee-haw scene at the beginning of the cattle drive, which is wonderfully edited, also figures prominently in a scene in the funny and entertaining Western comedy City Slickers (1991) starring Billy Crystal.

A lot of that editing was by Christian Nyby, who would go on to direct, especially a lot of TV Westerns.

Back from Institut Lumière, I have seen it on a big screen again. Still magic after all these years in spite if some weaknesses here and there, especially its sloppy ending. Over 2 hours through such a long voyage and after experiencing all these hardships for this, come on…!? But after all, the Odyssey has a “happy” ending…

You may find Joanne Dru’s speech silly but it announces Angie Dickinson’s one in Rio Bravo. Dru’s character is typical of Hawks’ feminine characters, Hawks women (Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Lauren Bacall or even Elsa Martinelli in more developed roles) always being one step ahead of the men and being a risk for the male group.

Brennan’s Nadine (!?) Groot announces (in a more subtle way) his Rio Bravo’s Stumpy. But I have always preferred him in My Darling where he shows much more what a great actor he could be.

It is always rewarding to revisit our classics.

For me the ending DOES work – I think it’s part of a dramatic coherence that holds the movie together.

Wayne makes a catastrophic wrong decision letting Coleen Gray go with the wagon train, so he pours his energy into building a cattle empire and his love into a son. His son goes against him – due to another wrong decision by Dunson – and he feels painfully betrayed. The Joanne Dru character starts to talk some sense into him and by the time he gets to Abilene he knows he’s wrong – he’s just too stubborn to admit it even to himself. What Tess Millay says to them is the truth – they DO love each other.

I tend to see the film as a drama about a stubborn man whose life is shaped at the beginning by a wrong decision and is almost destroyed 15 years later by a second one. People are always telling him he’s wrong but most of the time he won’t listen. The female characters are crucial – the first one he ignores, the second he listens to.

I reckon that’s a valid way of looking at it.

Bligh was cast adrift but survived.

It could also be that I am (too?) sentimental. I actually think the ending of The Searchers – “Let’s go home, Debbie” (which you mentioned in one of the comments) – is the BEST bit of the movie. So I seem to have a soft spot for characters at last finding emotional peace after a period of emotional turmoil.

I wonder how much we project our own personalities on to the movies.

PS. Good health for 2024, Jeff and all readers.

Oh, we project alright!

Happy New Year to you too.

It’s an interesting debate. My problem with the ending of Red River, and with ‘Let’s Go Home, Debbie’ in The Searchers is not with the basic idea – I too am on board for flawed characters embracing a bittersweet redemption (although in the case of Red River, Clift or Ireland actually killing Wayne would be a powerful conclusion!) – but with the way it’s executed. In both cases the Wayne character’s change of mind feels, for me, far too sudden, it feels like a writer’s contrivance rather than a plausible development in the character and the story. And in the case of Red River, I think the Joanne Dru character is in any case introduced a bit too late in the film, and her speech to Wayne and Clift feels like it wandered in from one of Hawks’s screwball comedies. So I’m afraid, for me, it does rather spoil, though not ruin, what until then is a pretty great movie. But I’m glad to hear that some people like it!

Wishing a Happy New Year to all.

I’m def with you on this and think you put it very well.

Hello, RR. That’s a very interesting comment. I think there are STRUCTURAL flaws to the movie. You mentioned the late introduction of the Joanne Dru character. I am always thinking ‘what IS the John Ireland character doing in the movie?’

With regard to Dunson’s change of mind – I don’t think it happens suddenly in Abilene, my feeling is Joanne Dru already talked some sense into him – he’s just too stubborn to admit it to himself.

I puzzle about these Howard Hawks women speeches too – “I make you mad, don’t I – you took one look and you thought – ” all that sort of stuff. It’s great fun but what does it actually mean?

PS. RR – you’ve got me thinking. I think the ending has dramatic logic – as I have argued – but you’re right, it’s badly executed. Thinking about it, it’s the TONE that has always jarred for me, not the logic. The tone is wrong for the film that led up to it – the reconciliation after her speech is played almost for laughs as if the long build up hadn’t happened. There should at least be a pause for it to sink into Dunson what’s been going on in his head.

By Jove, I think we’re close to agreement! You’ve made a persuasive case that Wayne and Clift reconciling is a justifiable denouement in terms of the relationship between the two characters – but we agree it’s fumbled in practice because of the sudden jarring tone shift.

Absolutely – thumbs up emoji.