Like Cooper and Wister, Grey was not a Westerner. Pearl Zane Gray (1872 – 1939) was born in Zanesville, Ohio, a city founded by his great-grandfather Ebenezer Zane. Soon after his birth his father, a dentist, changed the name to Grey, who knows why. As a boy, Pearl (he adopted the second name Zane later) loved baseball and fishing, and was an avid reader of James Fenimore Cooper and dime novels. He wrote his first story, Jim of the Cave, when he was fifteen. His father disapproved, tore it to shreds and beat him. Not the greatest start to a literary career. But the young man did get some writing published – not Western stories but articles on fishing in Field and Stream.

The boy extracted teeth as his father’s assistant until the state regulators intervened. Zane went to the University of Pennsylvania to study dentistry on a baseball scholarship but was only an average student at best. He started writing poetry. He was shy and teetotal.

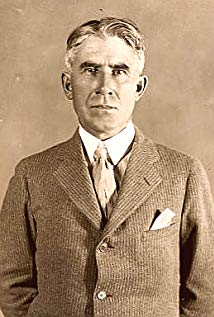

After graduating, Grey established his own dental practice in New York City under the name of Dr Zane Grey in 1896. In 1905, he married Lina Roth, better known as “Dolly”. He was often unfaithful to Dolly and it must have been hard for her as he suffered all his life from depression, anger and mood swings. He wrote: “A hyena lying in ambush—that is my black spell! I conquered one mood only to fall prey to the next…I wandered about like a lost soul or a man who was conscious of imminent death.”

Grey’s first published work was Betty Zane (1903), an historical novel about his ancestors. He could get no publisher interested and he had it privately printed. This was followed by Spirit of the Border (1906) and The Last Trail (1909), which were also, in the clumsy modern jargon, self-published. All three were financial flops. His style was often florid and his grammar inadequate, and Dolly did much proofreading and correcting.

In 1907, the campaigner to preserve the bison Charles ‘Buffalo’ Jones introduced Grey to the Southwest. Grey was entranced and he modeled several of his characters after Jones, including the central figure in The Last of the Plainsmen (1908). But Richard Etulain, the great expert on Western writing, tells us:

After reading the manuscript, Ripley Hitchcock of Harper and Brothers plunged in his editorial dagger. “I don’t see anything in this to convince me you can write either narrative or fiction,” Hitchcock told Grey. The comment, coming from a close friend of Buffalo Jones, was almost a death kell to Grey’s writing career.

.

Grey read Wister’s 1902 Western novel The Virginian and studied its style and structure in detail. He called his own works ‘romances’ and tried to model them not only on Wister but on Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, two of his favorite authors. From Scott he probably got a penchant for length, and a sentimental treatment of history.

He started traveling in the West, taking photographs and making detailed notes. “Surely, of all the gifts that have come to me from contact with the West, this one of sheer love of wildness, beauty, color, grandeur, has been the greatest, the most significant for my work.” And he added, in a comment that foreshadowed his most famous book, “That wild, lonely, purple land of sage and rock took possession of me.”

Unfortunately, his novels abound with such wordy descriptions of landscape, often delivered as the views of his heroes. He made copious notes on his travels and inserted them verbatim into his books, to the detriment of the narrative.

Nevertheless, he did stress action and plot, and this aspect eventually made his stories popular. He certainly had a storytelling power. He had learned the tricks of the romance-novelist’s trade, ensuring that his chapters abounded with cliff-hangers, mystery, conflict and climactic action.

Harpers finally accepted a Western novel from Grey, The Heritage of the Desert, in 1910, and it sold well. This was followed by a trio of books aimed at children, two of which, The Young Forester and The Young Lion Hunter, were vaguely Western (another was a baseball story). But of course it was in 1912 that Grey’s name was made.

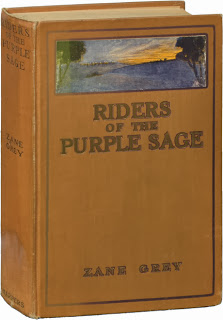

Riders of the Purple Sage was published in that year. It was a huge best-seller.

You probably know the story. In fact, though, there are two parallel stories (though unlike parallel lines, they occasionally intersect): everyone thinks of Riders, because of the movie versions, as the tale of the mysterious gun-man in black, Lassiter, who in Utah comes into the life of beautiful cattle rancher Jane Withersteen, champions her cause and steals her heart. But in fact a greater part of the book is devoted to the other story – how Jane’s rider (or cowboy) Bern Venters shoots the famous ‘masked rider’, sidekick of rustler Oldring, and discovers he has shot a girl. He nurses her back to health in a hidden cañon, falls in love with her and they eventually live happily ever after.

Today, quite frankly, much of Purple Sage makes pretty difficult reading. More than a century on from publication, we find the style melodramatic (Victoria may have been dead but Victorian melodrama wasn’t), prolix and sentimental to a degree hardly acceptable. It’s what you might call purple sage prose. Grey certainly loved the color purple and the word appears on many of the pages, used to describe the sage, mountains, land, sky and anything else to which might be attributed color. I must say, I have traveled quite extensively around southern Utah and northern Arizona and Nevada and I didn’t see much purple. The predominant colors seemed to be gray and orange. Sage is only purple when it blooms anyway. But I guess Riders of the Gray Sage wouldn’t have been all that romantic.

Dashes and exclamation points pepper the page as characters breathlessly open their hearts and spill out their emotions. Bess:

I was happy – I shall be very happy. Oh, you’re so good that – that it kills me! If I think, I can’t believe it. I grow sick with wondering why. I’m only a – let me say it – a lost, nameless girl of the rustlers. Oldring’s girl, they called me. That you should save me – be so good and kind – want to make me happy – why, it’s beyond belief.

And so on, almost ad infinitum. It’s overwrought and these days rather indigestible.

When his rough Westerners speak, Grey’s reading of Wister becomes regrettably apparent for they sound hokey and the vernacular is forced:

I jest saw about all of it, Miss Withersteen, an’ I’ll be glad to tell you if you’ll only hev patience with me,” said Judkins earnestly. “You see, I’ve been pecooliarly interested, an’ nat’rully I’m some excited. An’ I talk a lot thet mebbe ain’t necessary, but I can’t help thet.

Worst of all is the baby talk of the child Fay.

“Muvver sended for oo,” cried Fay, as Jane kissed her, “an’ oo never tome”.

People descry things rather than see them and inversion is overused (“No unusual circumstance was it for Oldring and some of his men to visit Cottonwoods in the broad light of day.”)

Well, it was 1912 and we mustn’t judge too harshly.

The advantage, stylistically, is that (thanks to Dolly and the Harper editors) the English is correct and clear. Grey could handle, for example, the difference between the verbs lay and lie, or raise and rise, which many modern American writers can’t, and he doesn’t use the preposition like as a replacement for the conjunction as, as many modern writers and speakers do (or like many writers do, to put it in the modern parlance).

Grey is uncompromising in his anti-Mormonism. The Mormons are very clearly the bad guys. Under the hypocritical cover of their religion, they steal, spy, covet, lust, kidnap and kill. Sometimes all on the same day. The Elder Tull and the Bishop Dyer, in particular, are very nasty and, in the best Western tradition, deserve the come-uppance that they will inevitably get under the guns of the good guys.

Movie versions of the book were mealy-mouthed about this and most excised the Mormon element of the story. The Tom Mix version had no Mormons and even the 1990s TV version with Ed Harris, for example, carefully avoids even the word Mormon, in the most PC way.

When Zane Grey was growing up, the Mormons, to many people, were anti-American. The Utah War was a relatively recent memory. Theocracy and polygamy were considered unconstitutional, immoral and essentially unAmerican. In addition, Grey had a faintly anti-clerical side and held broadly pantheistic beliefs. Utah Mormons made suitable opponents for decent, brave, simple American Westerners to combat.

Lassiter is described as “a hater and killer of Mormons”. He has devoted his life to avenging the corruption and abduction of his sister Millie by the sect. The Mormons have blinded his horse. The shooting of Dyer, though we only hear about it at one remove, described by Judkins, is a gripping moment when the evil hypocrite (whom Lassiter refers to as “the fat party”) gets shot full of holes in his courthouse. “Proselyter,” Lassiter admonishes him as the Bishop clutches the bullet holes in his body in a vain attempt to stanch the blood, “I reckon you’d better call quick on thet God who reveals Hisself to you on earth, because He won’t be visitin’ the place you’re goin’ to!”

However, the non-Mormons are pure. The ‘Gentiles’, as they are called, are all honest, decent upright people and the riders are brave and noble. The child Fay is absolutely angelic. Bess is virginal – and I love the way that she and Bern have separate caves in the hidden valley!

A sequel to Riders of the Purple Sage, which tells of what happened to Jane and Lassiter and their adopted daughter Fay, was published in 1915 with the title The Rainbow Trail, though I’ve never read it. It is said to be less anti-Mormon.

The impact of Riders of the Purple Sage on the Western genre was immense. It is impossible to imagine the novel Shane or the movie made from it for example, without reference to Riders. The lone, mysterious gunman (often dressed in black) riding in from nowhere and righting the wrongs in a community became a standard point of reference. Hondo is Lassiter – with Apaches instead of Mormons – and countless other Western heroes, on the page or on the screen, are Lassiter too.

The glorification of Western landscape was another influential feature. You sense that a writer like Louis L’Amour was greatly influenced by Grey (though far more economical in his writing). Western movies too reveled in the settings. We think in particular of John Ford and Monument Valley (also in southern Utah, by the way) but so many Westerns cared passionately about landscape, and the visual, photographic aspect of such movies is often fundamental. Have a look at Escape from Fort Bravo, Pale Rider (shot by Surtees père and fils respectively) or Silverado, just as a few examples of very many, and you will see what I mean.

The importance of the horse, also, is a seminal Riders theme. Jane’s thoroughbreds and the skill of the riders are written about glowingly. The race between Bern on Wrangle pursuing jockey Jerry Carn leaping at full gallop between the blacks Night and Black Star as they hurtle across the sage is one of the genuinely thrilling parts of the book. Actually, these mounts seem to have overdrive, or a fifth gear: I always thought, when I learned to ride as a boy, that the gait of a horse could be a walk, trot, canter or gallop. But the way Grey describes it, a run comes after a gallop and is even faster. When Jane presents the blacks to Bern and Bess to ride away to happiness on, it is a symbol of her giving up the past and her Mormon-inherited wealth and finding true love with Lassiter.

Particular elements of the story were taken up and used by the future Western. Cattle stampedes, of course, became a staple of the Western movie. Water rights, horse stealing and the discovery of gold all feature largely. In Chapter V the rustlers ride into their hidden lair through a waterfall. Watchers of Johnny Guitar or Randy Rides Alone will recognize that!

Riders of the Purple Sage was made into a movie five times. There was a silent starring William Farnum in 1918 (only six years after publication of the novel) and another silent with Tom Mix in 1925. The first talkie version was in 1931, starring George O’Brien, and ten years later George Montgomery led another. A TV movie starring Ed Harris came out in 1996.

It does make a good movie. Long novels have to be radically slimmed down for the screen but luckily Riders had pages and pages of soppy love and descriptions of nature that could be immediately discarded, and the novel’s action, which is genuinely good, would remain for the film. The same is true of The Last of the Mohicans, of course.

But I’d watch a movie version again. The Ed Harris one is the best so far.

Purple Sage made Zane Grey the most famous Western novelist of his time. From 1917 to 1925 Grey was never off the list of best-sellers, a feat that has not been equaled, and he became one of the first millionaire novelists. He never improved as a writer but he continued to churn out a couple of Westerns a year. In doing so, as Professor Etulain puts it, “he solidified the mold of what became known as the Western.” And we lovers of the ‘formula Western’ should be grateful to him – even if we don’t read him that much these days!

Many of his stories were made into Western movies, not only Purple Sage. We can go right back to Tom Mix’s The Heart of Texas Ryan in 1917, and another version of The Last Duane is in development right now. Robbers’ Roost, The Vanishing American, Western Union, The Lone Star Ranger, The Light of Western Stars, and many more, the list is a long one. Paramount in particular bought the rights to his books and hired Grey as consultant.

In fact Grey himself set up Zane Grey Productions in 1919 to make motion pictures from his stories but he found it too time-consuming and he hadn’t the requsite skills, so he sold the rights to Jesse Lasky for $25,000 a book, a huge sum then, and he was to get 50% of the profits. He was evidently a shrewd operator. He also had a clause in the contract which stipulated that the stories were to be filmed where they were set.

Lasky produced a series of (heavily adapted) silent Western movies in the 1920s based on the books which were remade as talkies in the 30s directed by a young Henry Hathaway and starring Randolph Scott. On TV, the Zane Grey Theatre series had a five-year run of 145 episodes from 1956 to ’61.

Zane Grey died of heart failure on October 23, 1939, at his home in Altadena. The last Western novel published in his lifetime was Knights of the Range but Zane Grey Westerns have continued to be published since. Harper had a stockpile of his manuscripts and continued to publish a new title each year until 1963. Then there were reissues, unabridged versions, and so on. He has sold over 40 million books. He is still widely read.

9 Responses

From my previous comment, Zane Grey wasn’t a favourite of mine, l can’t remember what book l tried to read way back in the 60s, maybe Riders of the Purple Sage, that’s such a great title. Also at that time Dell Comics were publishing a lot of Zane Grey titles, and they also did a series called Zane Grey’s Stories of the West, l much preferred these to the books.

RKO also made a very good set of Zane Grey films with Tim Holt, Robert Mitchum and James Warren, all worth seeing, especially the Mitchum titles.

I have never seen a Riders….. film, so must check out the Ed Harris version.

Yes, those RKO ones were fun. See https://jeffarnoldblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/nevada-rko-1944-and-west-of-pecos-rko.html

You'll enjoy any of the Riders movies, each one 'of its own time'. However, the first silent and the '31 and '41 versions aren't easy to find.

Jeff

I'm surprised you have never seen either the 1931 George O'Brien or 1941 George Montgomery versions, Mike, an old fellow 'B' enthusiast like you.

I agree about Grey's writing, which I find too wordy, though I like the stories and adaptations thereof. (Bit like Dickens actually). I found disappointment back in the day reading Clarence E. Mulford too, expecting his characters to be like the Cassidy films, which they weren't. I probably ought to give them another go now.

Enjoying this look at the writers, Jeff – great idea.

Yes, Mulford and Boyd's Hopalong are as far apart as you could get!

The great thing about written Westerns is that you get the whole spectrum, from lurid dime novel to literary masterpiece, and 'quality pulp' in between.

Jeff

I’m surprised to, years ago l had an NTSC tape of the George O’Brien version, but picture quality ruined the film, can’t remember if l even finished it to the end. The George Montgomery version has always eluded me. As no official release, l guess quality could be an issue with that as well.

If memory serves me, I have pretty decent transfers of both the 1931 and 1941 films, Mike.

Only the Tom Mix and the Ed Harris ones are available on amazon as DVDs.

Jeff

Jeff, I'm enjoying the fire out of these good write-ups on Western writers. We owe them much, so thank you to Zane Grey for giving the public something to read. In all fairness to Grey and his descriptions of the landscape. Most of his readers hadn't seen the land west of the Mississippi River, so he described it in length. Also, how much did wife Dolly contribute to the novels and Zane's BRAND? I think she made a huge contribution. For those who are interested, here is an article written by my late friend Dusty Richards. https://truewestmagazine.com/rider-of-the-purple-prose/ While you are there, go ahead and click on the article about George Montgomery and his real Western Colt revolver and its use for him in the reel Westerns.

Mike and Jerry, really good comments that I'm enjoying. Mike your list of Western writers are some of my favorites, especially Frederick Dilley Glidden(1908-75), better known as Luke Short. Several top notch Western movies were made from his writings. Western Movies, starring Randolph Scott, Joel McCrea, Rod Cameron, Robert Taylor, and others. Jerry, I like Clarence Edward Mulford's(1883-1956) Hopalong Cassidy books and William Boyd's Hopalong Cassidy movies. In my mind, I separate the two.

That comment about the Zane Grey 'brand' is a good one: there were so many spin-offs like comics, TV shows, etc., that Grey became far more than 'just' a writer.

I am the world's biggest fan of Luke Short Westerns.

Jeff