Hollywood crosses the Rio Grande

Oily craftiness

In the early days of the Western there was little but contempt for the Mexican. The BFI Companion to the Western tells us that “The Mexican heavy in Broncho Billy’s Redemption (1910) is given money to buy essential medicine for a dying man but instead steals the money and tears up the prescription. In The Cowboy’s Baby (1910), the Mexican throws the hero’s child into a river. By the time of Broncho Billy and the Greaser (1914) and The Greaser’s Revenge (1914), it went without saying that the Mexican was ‘an evil halfbreed’ and that (unlike WASP villains) he rather enjoyed it as well. Only after protests from successive Mexican governments (and even threats of a boycott) did the word ‘greaser’ disappear from movie titles.”

Mexicans and (even worse) half-Mexicans were the standard villains in William S Hart’s Westerns, “racially low” types in the Wister/Remington/Roosevelt scheme of things. For example, saloon keeper and racketeer Silk Miller in Hell’s Hinges (1916) is described on an intertitle card as “having the oily craftiness of the Mexican.” Mexico was thought of as some kind of rather corrupt country south of the border with civilization, really just a place for renegades to live. Racial stereotypes of all kinds were deeply entrenched, and that applied to Mexicans too. Even in much more modern Westerns, there was often one Mexican in a band of scurrilous Anglo outlaws; it was taken as read that he would be a bad guy.

.

.

There had been silent Cisco Kids in 1914 and 1919, but in 1929 Fox brought The Caballero’s Way to the talkie screen, In Old Arizona. It followed the Henry short story pretty closely, though they toned down the leading character’s villainy. Nevertheless, he was a charming rogue, amoral if not immoral, but that was OK because he was Mexican. Warner Baxter took the part. It was to have been a young Raoul Walsh, who would also have directed, but a jackrabbit through his windshield put paid to that, and to an eye. Baxter won an Oscar for it.

.

Later Cisco would get a sidekick (they were kinda de rigueur in Westerns then) and Gordito, later Pancho, would be a caricature comic-relief figure, one which might make modern audiences cringe somewhat. He and Cisco would ride the West (both sides of the border) generally doing good and helping out the poor and downtrodden. All traces of the wicked original disappeared. Cisco and Pancho became as American as the Lone Ranger and Tonto. And Mexicans would again and again be simply figures of fun in Hollywood Westerns, “Ay, caramba! seeming to be their only line.

Mexicans in Amercan Westerns improved, though. While some continued to be clownish (I’m thinking of the likes of Pedro Gonzales-Gonzales, who was often a kind of ‘stage Mexican’), other parts were taken by fine actors who gave us Mexican characters of integrity and courage. Helen Ramirez (the splendid Katy Jurado) in High Noon is a strong, independent woman with grit and pride. Anthony Quinn – Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca, born in Chihuahua – was a superb actor who was often magisterial in American Westerns. Jurado and Quinn combined in the fine if underrated Man from Del Rio. Pedro Armendariz was a favorite of John Ford. There are many others. So it wasn’t all bad. It got better anyway.

Pancho Villa

Western movies began concurrently with Pancho Villa’s revolutionary career, 1903 being usually given as the start-date for both. Hollywood (and by extension the American public) was fascinated and appalled by Villa in equal measure right from the get-go. Amazingly, Villa did a deal with an American motion picture company to film battles as they happened. He needed US support and gold, and the movie got him both. He really did agree to fight his battles in daylight and re-enact any that weren’t captured on film. The actual contract that Villa signed with the Mutual Film Company on 5 January 1914 to capture the battle of Ojinaga on celluloid still exists and is in a museum in Mexico City.

Tragically, the original movie, directed by the great Christy Cabanne and written by Frank E Woods in 1914, has been lost, like so many early films of inestimable historical value, although a few scenes still exist in the Library of Congress in Washington DC. There’s an interesting documentary about the lost reels made by the University of Guadalajara, Los rollos perdidos de Pancho Villa (click the YouTube link to see that) which includes some fascinating existing scenes. And in 2004 HBO came out with the well-made and enjoyable picture And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself, with Antonio Banderas as Villa, which told the story.

Remarkable footage

Pancho Villa would remain a popular subject for ‘Mexican Westerns’. In 1934 MGM made Viva Villa! David O Selznick hired the great screenwriter Ben Hecht to adapt Viva Villa!: A recovery of the real Pancho Villa, peon, bandit, soldier, patriot, a 1933 book by the English left-wing writer and sympathizer Edgcumb Pinchon.

The tale starts with the whipping to death of Pancho’s father by a cruel haciendado. This was a standard part of the Jesse James myth, as you know, and this screen Villa has something in common with screen Jesses. Pancho flees into the hills and he becomes a great bandit chief. In a rather un-Jesse-like way, though, he comes back and lines up some hanged men as a (necessarily rather silent) jury before executing the ‘Spanish’ landowners who have taken the land from the peones. This job is given to ‘Sierra’ (Leo Carrillo), a portrayal of Rodolfo Fierro, Villa’s sadistic private executioner. It was a very violent film for the mid ‘30s.

The film plays fast and loose with history throughout – Villa even becomes president – and vastly oversimplifies, but to be fair, it does start with a disclaimer. There is a posh dame, Teresa (Fay Wray, famous for King Kong the previous year) who announces in her first line with that clipped British accent that was felt to be required that she is very “gled” to see Pancho. Villa will later assault her, playing into the shock factor of a pure white woman being brutalized by a low native. The scene was cut from the version usually shown but it is key. Her (white) brother will later avenge his sister by assassinating Villa (“I’ll kill him if it’s the last thing I do!” – you could get away with those clichés in 1934) thus attributing personal, rather than political causes to the revolutionary’s death.

The location shooting in Mexico, the masses of extras and the battle scenes pushed the budget of the picture up to almost a million dollars, an astronomical sum for those days, but Beery was enormously popular, the subject was enthralling and the movie recouped its production costs in under a year. The film may be pretty appalling to us today but at the time it was nominated for four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Writing, winning Best Assistant Director. Richard Slotkin, in his Gunfighter Nation, says, “Viva Villa! was an extremely successful film whose images and narrative formula shaped all future treatments of Mexico and the Revolution.” Margarita de Orellana, in her book Filming Pancho Villa: How Hollywood Shaped the Mexican Revolution (translated by John King, Verso, 2009) shows just how much the outside world’s perception and knowledge of the Mexican revolution comes from the cinematic treatment of Pancho Villa. One of Villa’s rivals, Venustiano Carranza, for example, hardly gets a look in, even though he became president. Ask ordinary, even college-educated people in the US (or indeed world) street to name a Mexican revolutionary and it won’t be Carranza they first come up with, if they come up with him at all.

There were also Mexican films featuring Villa, such as ¡Vamonos con Pancho Villa! (1936), with Domingo Soler as Villa, and later ¡Pancho Villa vuelve! (1950) with Leo Carrillo (better known to Americans as another Pancho) as the revolutionary leader and Así era Pancho Villa (1958) with Pedro Armendariz as Pancho. Much later, Old Gringo (1989), shot in Mexico with Jane Fonda and Gregory Peck, was a co-production between Columbia and Estudios Churbusco Azteca which had a small part for Villa (Pedro Armendariz again). But these weren’t American Westerns. However, Pancho Villa would, we know well, return to the American screen (see below).

Benito Juárez

In 1938, four years after Viva Villa!, Jack Warner, with other members of the Producers’ Association, accompanied the US delegation to the inter-American conference in Lima, called to further FDR‘s ‘Good Neighbor’ policy. One of the projects that emerged was to become Warner Brothers’ Juarez (1939). Hollywood would now go back to the nineteenth century and look at earlier phases of Mexican revolutionary history.

Wilhelm Dieterle (1893 – 1972) was born and died in Germany but is thought of as a Hollywood film director. He came to the United States when he was 37, in 1930, and put his talents to work for Warners. He had long been an actor in and director of European films and had worked under Paul Leni, FW Murnau, Conrad Veidt, Emil Jannings and other luminaries of German expressionist cinema. At Warners he specialized in biopics and made films about Madame Du Barry, Louis Pasteur and Emile Zola, the last two with Paul Muni in the lead (Paul probably passed on the first one). It seemed natural that Dieterle and Muni should have a go at Juárez next.

John Huston, no less, was one of the writers. The screenplay was based on a play by Franz Werfel and a novel by Bertita Harding.

Benito Pablo Juárez García was a lawyer of peasant Zapotec origin who served as Mexico’s president for five terms from 1858 to 1872. As a young man he managed to gain an education and he became a lawyer, then a judge, and governor of the state of Oaxaca from 1847 to 1852. He was driven into exile (he worked in a cigar factory in New Orleans) because of his opposition to the autocratic and corrupt regime of President Santa Anna. At the fall of Santa Anna in 1855 Juárez became a leading figure in La Reforma, then interim President as Mexico wallowed in bloody civil conflict, before being elected in his own right. His leadership of the struggle against Napoleon III’s forces and the overthrow of Napoleon’s puppet the Emperor Maximilian is a famous one.

The Juárez of Dieterle and his writers, played by a heavily made-up Muni, is ethical, noble, almost saintly, and much is made of his admiration of and friendship with Abraham Lincoln, whom he tries to emulate in all but height (Juárez was a tiny man, 4 feet 6 inches or 1.37m tall). In the film he is often seen below a picture of Mr Lincoln. The movie is a thinly-disguised allegory of the contemporary (1939) geopolitical scene, as valiant Juárez, backed by a benevolent USA, fights for freedom against a foreign autocratic regime (that of the Emperor Maximilian).

But the film manages a neat trick: it makes the great opponent of Juárez, Maximilian, sympathetic too. The Hapsburg monarch is played by English actor Brian Aherne, who had made his Broadway debut in 1931 as Robert Browning in The Barretts of Wimpole Street. He was nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal of Maximilian and with just cause. His Emperor is no arrogant autocrat or extravagant philanderer but a sensitive person who sincerely tries to do the right thing by the population of his new country. So we have two upstanding protagonists.

Behind them, though, lurks the Machiavellian presence of Napoleon III. Claude Rains was the ideal, almost inevitable choice for the scheming, vain, unreliable ‘ally’. Gale Sondergaard makes his wife Eugénie almost as politically Machiavellian.

It’s a superb picture visually (DP Tony Gaudio was Oscar-nominated for it). The original music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold is also very well done, and cleverly incorporates variations on the themes of various national anthems when those countries are mentioned or a representative of that nation appears. While the plot is all rather simplistic, the story does generally more or less conform to historical fact, as far as Hollywood ever does. The American public took the Juaristas to its heart almost as much as it had Pancho Villa, and Hollywood would return to the subject.

Emiliano Zapata

But another Mexican revolutionary hero came along in 1952 when Marlon Brando starred as Emiliano Zapata in (a rather obvious title by now) Viva Zapata! It’s actually very good. The Elia Kazan direction is seriously classy and the black & white photography by Mexico City-born Joe MacDonald is luminous. Kazan and MacDonald together studied the famous Casasola photographs of the revolution.

The reserved Emiliano Zapata was a most interesting man, far more than the glorified bandit that the mercurial Pancho Villa was. Dandy, womanizer, true believer, Kropotkin-influenced communalist, superb horseman, courageous fighter, he was not Marlon Brando but while the film may not capture the real facts of the life of the man, it does somehow capture the spirit. History is always changed in Hollywood. Various scenes never happened. Zapata did not meet Porfirio Diaz in Mexico in 1909, for example. But a lot is right and the movie is closer to the reality than many. Kazan said, “There may be more historically accurate portrayals of Zapata in other films, especially from Mexico, but I think Brando provided a wonderful interpretation.”

The picture was something of a surprise in its left-wing agenda. MGM were going to make it but studio execs thought of Zapata as “a goddamn Commie revolutionary” and nixed the project. It was sold to Fox, and to that studio’s credit, the picture was granted serious resources. It is true that the movie soft-pedals Zapata’s socialist program, and its hero is an essentially American-liberal character, a democrat who refuses to take part in Stalinist dictatorship. Still, it was quite a daring film for 1952, the high-point (or should I say low-point?) of McCarthyism.

But is it a Western? Ah, there’s the rub. So many American movies notionally about moments in Mexican history were Westerns, especially those (and there were many) in which a gringo goes south of the border and takes part in the excitements. Viva Zapata! had no gringo role, for once, but the movie was certainly very American. Filmed in Texas (the Mexican authorities were unhappy with the treatment of Zapata and didn’t want it shot there), with Anthony Quinn (an American of Mexican origin) alongside Brando, directed by Elia Kazan, released by Fox and written by John Steinbeck, you couldn’t call it a Mexican film.

And Kazan went for a lot of Western imagery – guns and horses and big hats and so on. Furthermore, Slotkin points out that Zapata’s radical Plan of Ayala becomes in this film the classic “little piece of land” dream of the popular Western movie. Not only that: the script and Brando’s make-up highlight Zapata’s Indian identity, and his love of the white ‘redemptive woman’ (Jean Peters) somehow references white/Indian romances in ‘true’ Westerns such as Broken Arrow or Devil’s Doorway, with the death of the Indian partner (Zapata is assassinated at the climax of the film) neatly sidestepping 1950s problems of what was called ‘miscegenation’.

No revolutionary heroes

Between Juarez and Viva Zapata! Hollywood gave us other Mexican pictures, but without specific historical heroes: John Ford’s non-Western The Fugitive (1947) and John Huston’s superb and Oscar-winning semi-Western The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). The first, though based on Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, which specifically set it in Mexico, concerned a fictional Latin-American country (but it was Mexico alright) with Henry Fonda as a renegade priest suffering persecution at the hands of an anti-clerical government. Fonda was of course associated in the public mind with American populist heroes such as Frank James and Tom Joad, and he’d also been Young Mr. Lincoln and Wyatt Earp, both for Ford again.

Sierra Madre, Budd Boetticher’s favorite Western (that has to mean something) may not be a Western at all. On the set, Huston breathlessly said to Humphrey Bogart, “I think we’re making something special here.” Bogie replied, “Oh, shut up, John. It’s just a Western.” But again, is it? Maybe. It has unscrupulous capitalists as villains, as ‘proper’ Westerns often did, there’s a mining camp, gold fever, wilderness and there are guns. The Indian village is a sort of pastoral utopia. The youngest prospector returns to the States to pursue the classic Western dream of a peach orchard, a good woman and some kids. You wonder if that’s what Bob Dylan had in mind when he sang:

Build me a cabin in Utah

Marry me a wife, catch rainbow trout

Have a bunch of kids who call me Pa

That must be what it’s all about.

That was what a whole heap of Westerns were all about anyway – wherever they were set.

Pancho Villa would be back right enough – he was too colorful and entertaining for Hollywood to forget – but in 1953 we had a nice change when in Universal’s Boetticher-directed Western Wings of the Hawk, with Van Heflin as the gringo hero, the charismatic revolutionary leader was not Villa for once but the completely overlooked (by Hollywood) Pascual Orozco.

Orozco (1882 – 1915) was, as you probably know, an anti-Diaz Maderista who, however, fell out with Madero and joined Huerta, earning the undying enmity of erstwhile ally Villa. When Huerta fell, Villa and Orozco managed to campaign together against the new Carranza administration but Orozco was killed near High Lonesome in the Van Horn Mountains in an obscure incident involving horse stealing. So much for the history. Orozco was played by Noah Beery Jr, Wallace’s nephew, and in fact as a young ‘un (he was born in 1913) Noah had taken part in Viva Villa!, though his scenes were later deleted. He endows Orozco with charm and zip.

The revolutionary needs support to capture Juárez and topple Diaz (that part sounds more like Villa but never mind). Beery had played Mexicans before (e.g. The Light of Western Stars) and was rather good at it.

Adventurers out for what they could get

Most of the gringo characters in Hollywood Mexican Westerns were there for profit, whether they were gold-mining like Bogie in Treasure or Heflin in Wings, or they were ranch owners like Lorne Greene in The Last of the Fast Guns, or dealing arms like Robert Mitchum in Bandido! or Alan Ladd in Santiago (both 1956) – the latter set in Cuba but to all intents and purposes a Mexican Western – or whether they were adventurers and soldiers of fortune (often after gold) such as Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster in Vera Cruz (1954) or Rory Calhoun in The Treasure of Pancho Villa (1955). They may (or may not) eventually come round to ‘doing the right thing’ by the Mexican people but that was not their motive for going there.

Vera Cruz brought the gringo-adventurer-in-Mexico theme to a sort of peak, with Lancaster and Cooper (yes, even Coop!) as cynical mercenaries out for the main chance and ready to back either side (Maximilian or Juárez) according to which provided more profit. A few of the Mexicans in the picture are quite noble and decent, such as the Juarista General Ramirez, but most are there to be shot down in huge numbers. Mexican viewers of the film were so disgruntled at the portrayal of their countrymen (as the DVD Savant review put it, “Semi-childlike but treacherous peasants whose main function is to die by the hundreds at the hands of über-mensch gringoes”) that they rioted at the première and threw seat-cushions at the screen. Eli Wallach said that the Mexicans were so upset that they insisted that The Magnificent Seven (1960) be checked by Mexican censors, and indeed film makers after Vera Cruz had some difficulty getting permission to, er, shoot south of the border.

Coop had actually come straight to the Vera Cruz set from making another Mexican Western, the very good Garden of Evil, directed by Henry Hathaway. Coop was in the country for tax-avoidance reasons. While on one level Garden of Evil is just another gringos-in-Mexico movie, it is rather subtly done, a cut above the norm and vastly better as a Western than Vera Cruz

Another picture that was much better than Vera Cruz was with Mitchum (again!), The Wonderful Country (1959), probably the best film of Robert Parrish. Based on the novel by Tom Lea, it is an interesting movie. It has some action but is not really a shoot ‘m up Mexican Western. It’s quiet, subtle, deliberately steadily paced and really rather sad. Mittchum always thought of himself as a renegade adventurer and he was ideal for the role of Tom Brady, an American who would always be regarded as a gringo in Mexico and a ‘greaser’ in the US.

Pancho Villa was back in 1958 with Fox’s Villa!!, which now felt that one exclamation point wasn’t enough and two were needed. In this one Brian Keith plays the gringo adventurer and Rodolfo Hoyos Jr was Villa. It was a pretty conventional Mexican Western à la Hollywood and, honestly, unremarkable, though Keith was quite spirited.

American cowboy heroes had often been down Mexico way, of course. All through the 1930s and 40s the likes of George O’Brien in The Gay Caballero, Buck Jones in South of the Rio Grande, John Wayne in South of Sonora, Gene Autry in South of the Border, Hopalong Cassidy In Old Mexico, Roy Rogers in Bells of San Angelo, and many more, crossed over the Rio Grande to provide a slightly more exotic background to the same old plot. Even that was iffy as many were still filmed behind the studios in Hollywood, but they outfitted the characters in large sombreros and maybe inserted a bit of stock footage from a travelog or something. These Westerns tended to concentrate more on fiesta than revolución, and they often featured plump señoritas singing in cantinas.

The reverse could happen: ‘American’ American Westerns, i.e. ones set in the US, could still be filmed in Mexico. John Wayne, we know, was especially fond of those Durango locations, and perhaps the landscape was often more ‘Western’ down there. Some of it had to do with lower costs, of course.

Spaghetti westerns, when they came along in the 60s, were especially attracted to revolutionary Mexico, though they continued the trope of having the action seen through the lens of the gringo south of the border (just a rather more European gringo). Many of these films were set there and one of them, issued under various titles but usually known as A Bullet for the General (1967), was actually not all that bad. It wasn’t good, of course, but as spaghettis go, it almost got up to the level of acceptable. Leone’s also variously titled picture which he insisted on calling Duck, You Sucker, with James Coburn and Rod Steiger in 1971, was, however, back to low-quality standard. In a way, though, these films are doubly unWestern, because they are a European take on action not in the American West.

Some American Westerns were influenced by these spag numbers. One thinks in particular of 100 Rifles (1969), notionally set in 1912, with Burt Reynolds as (not terribly convincing) revolutionary Yaqui Joe and (even less convincing) Raquel Welch as Sarita, and black lawman Jim Brown as the ‘viewpoint chracter’, so we are back with an America-centered approach.

Pancho was back again in 1968, with Yul Brynner in a wig as Villa and, yet again, Bob Mitchum as the gringo, in Villa Rides (amazingly, no exclamation point). It was to have been written by Sam Peckinpah but Brynner didn’t like the ‘bad guy’ Villa that the script portrayed and Sam was dumped. By coincidence, or as a result, it was a really lousy movie. Mitchum would return yet again in 1972 as a gun-totin’ priest in a 1920s tale, The Wrath of God.

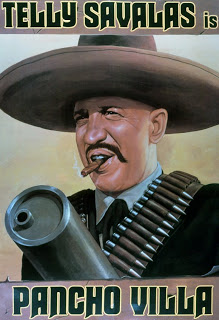

Pancho too would return yet again in 1972, in the unlikely form of another smooth-pated actor, Telly Savalas (well, they’d had a Mongolian from Brooklyn as Pancho, why not now a Greek? They’re all ethnic, ain’t they?) in what was, frankly, the worst of all the Pancho Villa movies, Pancho Villa. It was the year before Kojak, and Savalas was honing his New York accent for the tough cop act in readiness. He is embarrassingly bad. An alternative title was Vendetta and it’s basically a revenge drama. The ‘jokes’ depend on how amusingly Pancho shoots people. I really can’t think of anything good to say about this movie.

A mythic space

There were other ways in which Hollywood treated Mexico, and they were as a refuge and as a “little piece of land” dream.

In many a Western (and indeed in other genres) outlaws of one kind or another “head for the border”. Crossing the Rio Grande extracts them from US jurisdiction and brings them to safety. It’s what I call the Four Guns Syndrome. In Four Guns to the Border (1954) a band of (not very good) bank robbers headed by Rory Calhoun – the other three are George Nader, Jay Silverheels and John McIntire – head for the Mexican border to escape capture. This plot was done again and again. In The Last of the Fast Guns (1958) hero Jock Mahoney finds famed Hollywood gunmen Johnny Ringo, Jim Younger and Ben Thompson hiding out there. The outlaws don’t always make it. If they do, sometimes a lawman will cross over into Mexico in pursuit and bring the villains back to the US (think of The Last Sunset – Aldrich again – or The Ride Back – Aldrich as producer – or very many others).

In Stagecoach (1939) the Ringo Kid (John Wayne) and Dallas (Claire Trevor) cross the border over into Mexico at the end to evade the law – Ringo has escaped from prison and just killed the Plummers. But it is also to find that “little piece of land” again. They weren’t the only ones. Mexico (California served the same function – think Hondo or The Tin Star) was the ‘new West’ or the ‘even-farther-West‘ (click the link for our essay on that subject), a place where you could still ‘make it’, the place the Western frontier used to be, till it got too civilized. Heroes talk of a ranch where they can work and live in peace.

So Mexico functioned in American Westerns as an ‘other’ land, a place of haven or escape. But often in these cases it was only at the end of the tale, or maybe they didn’t even make it at all. Little if any of the movie took place in Mexico. It was just ‘what happened afterwards’, an epilogue to the story.

Illegal entry

In both Rio Grande (1950) and Major Dundee (1965), The Undefeated (1969) too, it isn’t just an epilogue. It’s the main plot. Americans under arms cross over into Mexico illegally or improperly, in the case of the first two to pursue Apache marauders. The heroic mission to rescue the children from the church in Rio Grande was turned on its head by director Robert Aldrich and his writers four years later in Vera Cruz, when Lancaster’s henchmen lock Mexican kids up in a church and use them, to the great disgust of the Juarista general, as hostages.

Strode, Marvin, Ryan, Lancaster: professionals

In Columbia’s The Professionals (1966) Lee Marvin leads a squad of mercenaries over the border to rescue a woman kidnapped by a Mexican revolutionary and bring her back. It’s quite amusing to observe in these pictures that the actors ride from right to left when going from the US to Mexico and cross the screen in the other direction on their return.

Slaughter

In The Wild Bunch (1969) Peckinpah had his dinosaur gunslingers take refuge in Mexico after their failed and very bloody bank robbery and there they get involved with local politics, coming up against the cruel, corrupt and drug-crazed General Mapache (the great Emilio Fernandez). After, once again, a Mexican idyll of village life, the American gunfighters perish in a last fight, but not before they have slaughtered huge numbers of Mexicans. Only Edmond O’Brien’s character, Freddie Sykes, escapes and joins up with the rebels/revolutionaries, to continue the fight for justice.

Slaughter

In Two Mules for Sister Sara, too, the year after, Mexicans are mown down in huge numbers. There seemed to be an idea that since now it was infra-dig to slaughter ‘redskins’, Native Americans having been rehabilitated by Hollywood and even become the goodies, it was OK to use explosives and Gatling guns to kill endless droopy-mustached men in tan uniforms instead. After all, they were unshaven. And foreign. They couldn’t even speak English.

In The Magnificent Seven (1960) it had been OK to kill endless Mexicans (Calvera is said to have forty men but if you count the number shot – not that I would be nerdy enough to do that, of course – you find it’s way more than forty) but then, you see, Calvera’s men were marauding bandits who extorted the wholesome (and remarkably clean-clothed) villagers. The bandidos deserved it.

Mexico had simply become a new theater of conflict, a place for American gunslingers (nearly always goodies, or at least semi-goodies) to show their prowess.

Mexican Westerns (if Westerns they be) are still going on. You could argue that Banderas’s El Mariachi pictures (starting 1995) are ‘Mexican Westerns’. In Cristeros (2012), aka Outlaws, we went back to the 1920s and the subject of the anti-clerical Mexican regime, as Andy Garcia as General Enrique Gorostieta Velarde battled the cruel dictator Ruben Blades as President Plutarco Eliás Calles. In these, though, when white US Americans appear at all they are peripheral, and both goodies and baddies are Mexican. That’s some kind of improvement, I guess.

Well, the list of movies mentioned isn’t exhaustive. You’ll probably think of others. But it’s enough to get a flavor of the ‘Mexican Western’ and reflect on Hollywood’s take on what happens or happened across the Rio Grande.

In so many films the American gunmen come to Mexico in a time of upheaval and social disorder (revolutionary or not) and help the locals defeat some bandit or warlord. They are completely superior, and the Mexicans couldn’t possibly have succeeded on their own. Often the Hollywood heroes woo a fair Mexican maid while they are there. In the end, it’s all pretty formulaic. It’s just that the formula is very slightly different from the standard Western movie set in the US.

You can find in the index a companion piece to this article, Canada: the American Western north of the border.

9 Responses

A very fine piece and a nice diversion from reviewing specific films.

A couple of points I recently saw Clint Eastwood's THE MULE which I consider his

best film in ages. I was very impressed by Clifton Collins Jr who plays the

nastiest of the Mexican drug cartel guys-especially with his cowboy hat and lean

frame,he reminded me of Dennis Hopper in his prime. I got to thinking how great

this guy would be in a Western. With research I found out that Mr Collins is in

fact the grandson of Pedro Gonzales Gonzales and by all accounts was very proud

of his grandfather. I hope somebody casts him in a Western someday,meanwhile he

will appear in Tarantino's ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD as "vaquero"

I should imagine Tarantino will be thrilled to have the grandson of an actor

who appeared in RIO BRAVO in his movie. Another draw,for me, is the the

forthcoming Tarantino film also includes Bruce Dern and Clu Gulager.

Anyway,enough of that-I recently got the restored Blu Ray of THE LAST COMMAND

and found the commentary by Frank Thompson most informative.

One fact I never knew is that the Mexicans opposed slavery and wanted to impose

the abolition of slavery on to the Texans and indeed the Americans,bearing in

mind both Travis and Bowie were slave owners.

Another thing I liked that Thompson said, was when approached by some people doing

a featurette on The Alamo they asked about authentic costumes.

Thompson replied that the costumes in most Alamo movies are inaccurate,more like

those in 50's Westerns-for a reference point Thompson asked them to take

"A Christmas Carol" as a guide.

Finally Mexican bandits pop up in countless Spaghetti Westerns,I guess because

most of them were shot in Spain,and it's easier to fob off the buildings and

landscape as Mexican.

Thank you, John.

There is now of course a whole genre of drug cartel movies, often involving Mexico.

I always liked Pedro G-G in Westerns, even if he was a bit of a stereotype.

Yes, the slavery angle is usually quietly glossed over in American Alamo pictures!

Jeff

Great article about about one of my favourite western film themes, films set in the USA, Mexico borderlands. One of my all time favourite borderlands films is The Wonderful Country with Robert Mitchum, plus of course many of the films mentioned in the article. A book could be written about the subject.

Talking of books, John Knight mentioned Frank Thompson. He wrote a great book called Alamo Movies many years back, hard to get now, but well worth seeking out.

As for those Mexican bandits in the Spaghetti Westerns, they were mostly played by the Spanish gypsies, who were probably glad of the handful of pesos they got for riding around in the hot sun of Almeria.

I too am fond of The Wonderful Country. See https://jeffarnoldblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/the-wonderful-country-ua-1959.html

Jeff

On this vast and exciting subject may I add a little more …

Although from cuban and spanish ascent I cannot resist to add a word about Cesar Romero playing the fourbe, treacherous, but classy and charming French officer – even if I know that Vera Cruz is not Jeff's cup of tea, sorry for him… – He had all the virtues and qualities to play a Mexican.

Also Ciudad-Juarez born Gilbert Roland – wondering if he was still on the border for the mexican civil war events… – has played with a Lewis machine gun in The Treasure of Pancho Villa and offered a Browning one to Bob Mitchum in Bandido.and this blog's reader for sure know how much Jeff is rightly fond of him…

The 1914 Mutual film was one of the first Raoul Walsh's step as a director. If you donot read his mémoires look for instance at

https://truewestmagazine.com/panchos-lost-film/

I was visiting Columbus NM in June 2018. Beside of a charming museum hosted in the former depot, several sites and plaques recall the Villistas raid. I hope that the Crawford affair or the later Pershing expeditions will become a film one day. I would also mention Tommy Lee Jones who to me embodies this twin culture region – remind you his Three Burials shot partly in the Rio Grande canyons of the wonderful Big Bend National Park.

We could also talk of the Durango region, scenery of countless films

Have a look for instance here

https://www.visitmexico.com/en/actividades-principales/durango/have-fun-like-a-child-in-the-old-west

Thank you again Jeff for this passionate text showing also the close connection between the 2 countries

JM

Thanks, JM!

I should def have mentioned those Tommmy Lee Jones Tex/Mex pictures.

I loved the True West article on Walsh and Villa. Thanks for thr link!

Jeff

Jeff, You wrote a good even-handed write-up. I think a lot of Western movies were set in the USA/Mexico borderlands, because of the landscape used to film them. Southern California and Arizona are similar to Mexico, anyway in Hollywood's lenses.

Yes, I should have mentioned the locations. One thinks especially of those big John Wayne Westerns shot down round Durango.

Jeff

At some moments in history, south of the border was much farther north…

Maybe you could think of developing a specific essay dedicated to Texas!? Wether in fiction or in history, the Lone Star State, proud to be unum in the middle of pluribus, is a huge source of stories and myths from Alamo to the border wars.

I fully agree about mentioning the movies locations. Almeria area in Southern Spain, previously seen in peplums like Cleopatra, french foreign legion or war films set in Northern Africa (Un taxi pour Tobrouk), has been extensively used in the 1960-70s westerns (spaghetti or not) not only because of the looking american scenery – the Tabernas badlands desert -, the western towns replicas or the extras looking like Mexicans, but also because it was cheaper.

US productions went to Mexico too and later to Alberta for the similar reasons.

JM