.

The thrill of the weekly serial

Although most serials were produced on very low budgets, and even the unsophisticated viewers of the 1940s would probably have scoffed at the wobbly scenery and the rockets on string, some were made at significant expense. Universal’s Flash Gordon serial for example, was reportedly budgeted at a million dollars, and while Republic’s Adventures of Red Ryder was hardly that, it was still no ultra-cheapie Z-movie. Far from it.

On his website, Jerry Blake says, “Adventures of Red Ryder ranks as Republic’s best Western serial, and also as one of the studio’s best chapterplays regardless of genre. It’s full of the continual but varied action scenes and memorable chapter endings typical of Republic’s Golden Age efforts, and is further enhanced by vivid characterizations and a script that manages to give added interest to standard B-western plot devices by incorporating them into a narrative far more compelling than the serial norm.”

We know quite a lot about the production of Red Ryder because one of the serial’s directors, William Witney, wrote an entertaining memoir under the title In a Door, Into a Fight, Out of a Door, Into a Chase: Moviemaking Remembered by the Guy at the Door, McFarland & Company, 1996, republished in paperback in 2005, and a very good read.

I say Witney was one of the directors because duties were shared with his great friend John English. They directed on alternate days, liaising in a bar every evening to ensure continuity (among other things).

In a New York Times interview with Rick Lyman, Quentin Tarantino singled out Witney as one of his favorite directors and a “lost master”. Certainly Witney knew what he was doing, as did

English. As far as Westerns go, Witney started as an extra on an oater in 1933 and first directed (with English again) on a Zorro serial in 1937, graduating to Crash Corrigan second features and Republic’s version of The Lone Ranger in 1938. Later he would be a regular helmsman of Roy Rogers oaters (and wrote another book about Trigger). He was still going strong in the mid-60s when he directed three Audie Murphy Westerns. English, who was exactly that (he was born in Cumberland, England in 1903, though he grew up in Canada), was also still directing in the mid-60s, mostly Western TV shows, but he started as an editor on Kermit Maynard flicks in the 1930s, graduating to directing Kermit in The Red Blood of Courage in 1935, the first of a long series of Maynard oaters. Witney and English were reliable and experienced hands who knew exactly how to make a Western rattle along at the gallop. They made seventeen serials together!

Five writers contributed to the screenplays of the ‘chapters’, adapting Stephen Slesinger and Fred Harman’s original NEA newspaper feature: Franklin Adreon was also a director and producer, notably of Mysterious Doctor Satan; Ronald Davidson was a writer and producer, known for Captain America; Norman S Hall wrote Adventures of Captain Marvel (and the 1933 John Wayne Foreign Legion yarn The Three Musketeers); Barney A Sarecky had been a producer of the Tom Mix serial The Mirace Rider; and Sol Shor wrote the likes of The Crimson Ghost, Radar Patrol vs. Spy King and King of the Rocket Men. These men were no unschooled amateurs. They knew exactly how to script a serial.

Witney wrote:

.

Witney tells of how Dave Sharpe was to act as Red Ryder having a fight with a heavy on top of a stagecoach. He then had to fall off the hurtling coach. “No stuntman likes to do a fall on flat ground. If there is a hill to roll down after they hit the ground, they can give you a more spectacular fall. … I was kidding him when I said, ‘Dave, that big sandy hill looks like a big feather bed. You should be able to do a flip or two in the air before you tumble down the hill.’ Dave didn’t laugh. He studied the hill, took a couple of puffs of his cigar, and said, ‘Will you settle for one?’” The stunt looks great in the serial.

The big question was, who would play Red Ryder?

“We were looking for a lean, craggy-faced western type about six foot six.” They found a kid to play Little Beaver. His name was Tommy Cook, 9, in his first role. They thought a very tall hero with a very short sidekick would be good. But they didn’t get a choice. Republic studio boss Herb Yates cast Don Barry. Yates thought Barry would be the next Cagney, short and feisty. Witney wrote, “As far as we [Witney and English] were concerned, Don stunk.” He added, “He was too short to play the role and his brain matched his size. The only thing that he had that was big was his ego. When the picture finished we decided not to have out usual party. The picture hadn’t been pleasant. Jack [John English] and I went across the street to have a drink. [Jack said] ‘God help the next poor directors who have to work with him.’”

Still, they had to make the best of it (though contracts for future Red Ryder actors contained a clause stipulating that they must be over six foot). Actually, though I know Barry was famously full of himself and not at all a team member, I don’t think he’s too bad as Red. He’s energetic and agile, and gives it his all. I also like the way he gives the odd smile to Little Beaver or generally lightens the tone here and there.

William C Cline in his account of the serial genre In the Nick of Time, said of Barry, “With a jaunty carriage and high-pitched husky voice that clipped out his lines in an unmistakably authoritative tone, the swaggering young hero brought to mind as much as anything else a confident, self-assured gamecock.”

Barry would of course be billed as Don ‘Red’ Barry for the rest of his career, rather to his chagrin.

Witney and English moved on to another Slesinger/Harman hero, King of the Royal Mounted.

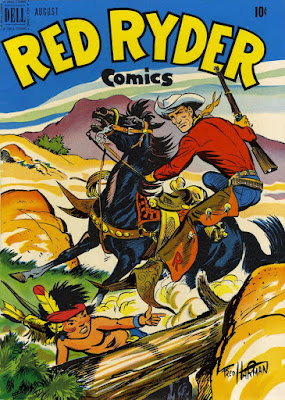

In the opening titles the comic ‘comes alive’ and we see Red Ryder galloping along on Thunder.

Chapter 1 (they were called chapters, not episodes) was Murder on the Santa Fe Trail. It’s 1870. We meet crooked saloon owner (was there any other kind?) Ace Hanlon, played by the great Noah Beery Sr, who had specialized in Western villains since the silent days. He manages to steal most of the scenes he is in with facial expressions, his large cheroot, and so on. Ace Hanlon’s place has a helpful sign above it reading ACE HANLON’S PLACE.

And we meet Calvin Drake, a pencil-mustached banker in a suit whom we identify in about 0.1 nanoseconds as a baddy too, and of course Drake and Ace are, yes, in cahoots. As with many of these serials they have a secret passage linking their two offices so that they can plot villainies together. Drake was played by Harry Worth, who had been a successful actor in British silent movies in the 1920s, come to the US in 1929 and started to take character parts in Westerns beginning with Hopalong Cassidy epics in the early 30s and continuing right up until a small part in Warlock in 1959. Ace is the dumb-ox kind of villain while Drake is the scheming Machiavelli type. But of course they are equally crooked.

Ace has a splendid henchman named One Eye who has, well, one eye. The other is covered by a patch. He looks excellently bad. This was Bob Kortman, who began his career acting in William S Hart pictures in 1915 and went on to support such actors as Gary Cooper, Buck Jones, Tim McCoy, Hoot Gibson and Johnny Mack Brown. He was Magua in the Harry Carey version of The Last of the Mohicans. And Ace has loads of other henches too, with names like Slim and Pete and so on. They will do his dirty work for him. They really are a bad lot.

Great news, pards. A leading henchman (until killed in Chapter 2), the sullen but crafty Shark, is our old pal Ray Teal! I’ve been a lifelong Teal fan and was delighted to see a young Ray (already stocky and already with that mustache). Actually, pretty well all the bad guys have mustaches. He had been ‘Henchman Pete’ in Zorro in ’37 but this was only his fourth Western in a career that would count 375 appearances in the genre, big screen and small, and last until The Hanged Man in 1974. And he has a nice big speaking part, and carries out much villainy, including kidnap and grand theft stagecoach.

It’s the old (very old) plot about the villains wanting the whole valley, using raids and barn-burning to force poor ranchers to sell because they know that the railroad is coming through there, and once they own the land they can demand any price they want from the Western Pacific.

Red Ryder’s dad, a local cattleman, tries to organize resistance to this marauding. Good news: Ryder Sr. is played by William Farnum, Dustin’s brother, veteran Western actor of the very early days (he had led the first version of The Spoilers in 1914 and would do key Westerns such as The Last of the Duanes and The Lone Star Ranger (both 1919) and would appear in the 1923, 1930 and 1942 remakes of The Spoilers. Sadly, though, Bill Farnum’s appearance in the serial was limited to Chapter 1 because the bad guys do him in, causing Red to want revenge, natch.

Actually, the walk-down to the saloon, where Red will brace the three murderers (Joe De La Cruz and Charles Thomas as well as Ray) is rather well done, and would have been worthy of a more ‘serious’ Western. The thugs gulp in close-up before the gunplay.

It’s RIP for two of them but Shark is arrested. Unfortunately, the local law is in yet more cahoots with the bad guys and the plan is that Shark shall not remain incarcerated long. Little Beaver overhears the plotting. He will do this overhearing pretty well every episode – I mean

chapter – and thus prove very useful to his pal Red. I think overhearing was his raison d’être. He rides quite well (he had apparently never ridden before this; Witney taught him) but his horse, Papoose (as followers of the comic and radio would have known) is never named in this serial.

By the way, the crooked Sheriff Dade is a young-looking Carleton Young. You remember Carleton. He was the one who delivered the famous line in The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” He was in loads of Westerns, big screen and small, and you can spot him in other John Ford pictures, and many other Westerns too.

Shark grabs the fair Beth (Vivian Austin) and hijacks the stage to abduct her (a pretty lowdown trick, you will agree) and, informed by Beaver, Red gives chase, allowing the chapter to end with a real cliffhanger. Cliffhangers were, as you know, an integral part of these serials. This one is almost literally a cliffhanger. The stage teeters on the edge of the abyss, with Red and Beth inside (and Shark too, actually). Will they all fall to their doom? NEXT WEEK…

In fact Beth as the leading lady hardly gets a look in, and in most chapters doesn’t appear at all. She was a perfunctory presence. Certainly there is no lovey-dovey between her and Red. Most of the small boys in the audience probably thought that was a good thing.

Chapter 2, Horsemen of Death (they have pretty racy titles, these chapters) starts with a recap, and what with the opening titles and credits and the closing ones, the screen time of the actual story is pretty limited, so they have to cram the action in. There has to be a horse chase every time, that’s de rigueur, and a fist fight (at least one) and of course they have to explain how the hero got out of the cliffhanger jam at the end of last week’s.

We go to the Circle R, the Duchess’s ranch. This Duchess (Red’s aunt, as you know) is played by fourth-billed Maude Allen, who had been in a 1930s Whispering Smith epic or two. She is suitably formidable. I said formidable, not fat.

On the ranch is also Red’s sidekick Cherokee, played by none other than the great Hal Taliaferro. Born in Wyoming, raised on a ranch in Montana, Hal was a real cowboy who got work as a wrangler for Universal Pictures, then entered films as an extra in 1915. By the 1920s he was starring in silent Westerns under the name Wally Wales (he took over the horse Silver King from Fred Thomson). His career declined when talkies came in, and in the mid-1930s, he changed to a new stage name, Hal Taliaferro, and worked in supporting roles for the rest of his career, primarily in Westerns. He has been called “one of the greatest stunt men in the game”. His last oater was 1952. He retired to his family’s property in Montana and devoted himself to landscape painting. As Cherokee he wears buckskins and says things like “Well, I’ll be dad-burned.”

“Who is your boss? Who killed my dad?” Shark is just about ready to spill the beans to save his own skin. “I’ll tell you. It was –“ Bang! Yup, Shark is silenced for ever (bye, Ray, thanks). Red chases the assassin (naturally) but falls from his horse and the posse is thundering down on him as he lies there. He’ll be run over! Oh no!

Chapter 3 is Trail’s End. Don’t worry, Red wasn’t run over. Cherokee saved him. We learn more about the shenanigans of the slimy banker Drake. He really is a skunk. He pretends to want to help the poor ranchers, all the while organizing attacks on them so that they will sell up cheap in despair. He agrees to put up money for a fund to help them and then arranges for the cash to be stolen in a stage robbery. Red and Cherokee thwart this wicked scheme. Drake and Ace don’t quite say, “Curses, foiled again!” but nearly, and they certainly look pretty cross. That is until they manage to steal that money after all.

Anyway, there are more chases and a mine, and One Eye tries to crush Red with an ore truck (in a scene lifted from The Lone Ranger). There’s no doubt about it. This time there’s no way out for Red. He’s a goner…

Chapter 4, Water Rustlers, concerns the heinous plan Drake and Ace cook up to stop the Duchess getting her cattle to market. You see, she has mortgaged the Circle R to the bank, to give money to the ranchers. But if her cattle have no water, they will die and the loan can’t be repaid. That will mean Drake will get the ranch, and be able to sell the right-of-way to the railroad. So Ace orders his henchmen to poison the waterholes. Little Beaver overhears them, though, obviously, and tells Red. Also, he undoes the girths of the bad guys’ nags and ties their saddles to a tree, so that when they try to gallop off, we get a comic fall. It works every time. This week’s cliffhanger is pretty spectacular, when the thugs burn down the water tower, and Red is lying beneath it as it falls! It’s curtains, surely!

Chapter 5, Avalanche, is another gripper. Red’s escape from last week’s danger is rather lame, though. He just gets up and runs away. Oh well. There’s a good bit when Little Beaver tries to get an apple out of the barrel, falls in, then overhears (as per usual) the bad guys hatching their nefarious schemes. The bad guys find him, though, and hold him hostage in a barn. Luckily, Red comes to the rescue. Red now wants to drive the cattle through Sundown Pass, to land with good water, but the villains have barrels of powder, marked Powder, with which they plan to bring the rocks crashing down on the poor moo-cows (and the drovers). Re-enter Beth. She is galloping along just as the gunpowder is about to go boom. Will Red be able to save her in time? Your guess is as good as mine.

Chapter 6 bears the sinister title Hangman’s Noose. Red does a deal with local rancher Ed Madison (Ed Brady) to use his water, but Drake has a loan out to Madison who is behind with the payments. Uh-oh. The banker demands immediate repayment in full or – yup, foreclosure. The good guys need money, and fast. Luckily, there is a stagecoach race that day, with the prize of exactly the amount Madison owes. Red will enter. But Ace arranges skullduggery, obviously, and Red is captured and imprisoned in a cabin. Cherokee has to take the reins. He is the day again. He throws .45 cartridges down the chimney of the cabin into the stove, allowing Red to escape and gallop to the stage race. Cherokee has been lassoed off the box but Red (or his stunt double anyway) leaps aboard, takes the reins and looks like winning. But then a bad guy ropes him and drags him away from the reins!

Don’t worry, he got out of that one. Chapter 7, Framed, shows us. He won the race, and got the money. Curses, think Drake and Ace, foiled yet again. But now Ed Madison is murdered and woe, Red gets blamed (by the crooked sheriff, of course). Cherokee helps him escape. He doesn’t run, though. We see him disguised as an Indian in town, trying to find the real killer (one of Ace’s thugs, of course). Well, he finds the rat and holds him, and there’s a good bit where he whittles a little wooden man and threads a string noose about the doll’s neck, and all the while the thug (Ernest Sarracino) gulps. Finally he snaps. He scrawls a confession on the table top and signs it. Great. Red makes to leave the cabin. But the nasty sheriff has arrived with a posse. Bang! The figure in the doorway slumps, shot.

Chapter 8, Blazing Walls, a good one, shows us that it was not Red who went through that door but the evil Grimes, who got no more than he deserved. I won’t go into all the ins and outs (amazing how many there are in fifteen minutes) but as you may imagine there are chases and fisticuffs galore. It ends with Red and Cherokee in jail, and the place is on fire. Red is very brave and manages to save Cherokee but just then a burning beam descends from the ceiling with a crash. Will they survive? Actually, the fire got out of hand and destroyed nearly all Republic’s jail set, which probably didn’t please Herb Yates, but it does make the scene more realistic!

Chapter 9, Records of Doom, describes how Drake says he has sold the loans on to an Eastern land company, S&S, and it’s out of his hands now. They will foreclose unless the loans are repaid in full by 6 pm today. Actually, he and Ace have set up this company. Red and the Duchess managed to get those cattle to market and the cash is coming in on the stage. Red and Cherokee gallop out to meet the stage and bring the money in faster. One Eye sets out to stop them. But despite the disgraceful misbehavior of One Eye, they get the money in at one minute to six. Phew! Now, who owns this durn S&S company? Details will be in the County Record Office. If Red can just get hold of those records… Another cliffhanger ensues.

Chapter 10, One Second to Live, a slight exaggeration, to be honest, describes Red escaping from certain death by dynamite, getting the drop on One Eye and Ace in a cave, Drake coming to join them but being warned just in time, so Red does not see who the Mr. Big is, and another dramatic chase. It’s all coming to a climax now.

Chapter 11, The Devil’s Marksman, is a deeply tragic one, for we must say goodbye to good old Cherokee, gunned down by the evil One Eye. Red says his goodbyes to the corpse of his old pard and sets off to exact revenge. One Eye and Ace shall smart for this! There’s a good quick-draw showdown, and you may guess who outdraws whom. Red has used Cherokee’s gun, and now cuts a last notch on its handle before smashing the pistol to pieces. But, and it’s a big but, the real villain, banker Drake, is finally unmasked! You do wonder why it took Red twelve weeks to catch on when we decided that about 20 seconds into Chapter 1. Oh well.

Chapter 12, the last one, Frontier Justice, tells how Ace and Drake get their come-uppance (for they inevitably do) and how their criminal schemes will be thwarted and how all will end well as ends well. Which it does. But not before a dramatic fight on a rope bridge and everyone thinking Red is dead. Red dead? No way.

The kids probably all went home happy and would be back the following Saturday to see Flash Gordon conquer the universe or something. Most satisfactory.

William Nobles was DP and he made the most of some attractive locations such as Iverson’s Ranch, Republic’s most common Western filming location, the area around Lake Sherwood, Beale’s Cut and Kernville (for the rope suspension bridge).

The DVD is quite good, the quality of the image being not at all bad for a 1940s serial eighty years on. The sound too. The music is actually quite interesting. Red’s tune is Oh, Susanna, and while for much of the show generic music from other serials is used to signal ‘danger’, ‘villainy’, ‘the chase’ and so on, when Red appears there are quite classy orchestral variations on the theme of Oh, Susanna, by whom exactly is not clear: three are credited with the music, Cy Feuer, William Lava and the great Paul Sawtell. I think Cy did the Oh, Susanna bits. Perhaps the idea was to associate the music with Red Ryder in the same way that Rossini’s William Tell Overture did for the Lone Ranger.

The producer was Hiram S Brown Jr. He also produced several other Republic serials, Fu Manchu, Captain Marvel, Jungle Girl, and so on. Here’s a photo of Brown flanked by directors Witney (left) and English (right):

3 Responses

Wild Bill and Bobby Blake coming from behind a picture book; once having seen them, no one else will do.

Yes, we all have our favorites!

If you believe my comment in error, correct me. No comparison between Bill Elliott's Red Ryder films Allan Lane's, Don Barry's serial and certainly not |Jim Bannon. I am referring to both production and box office business; it is why Wild Bill was kicked upstairs into bigger budget projects.