Quite a trip

.

.

I read on the subject a 1998 essay, The Western under Erasure, by Gregg Rickman, published in the collection The Western Reader, edited by the same Rickman and Jim Kitzes, Limelight, 1998. I’m afraid it was rather too intellectual (and too long) for my tastes, middle-brow being about as far as I go, and a lot of it smacked of the dreaded ‘film studies’. Still, there were nuggets in there, and some food for thought (I think I’ve just mixed a metaphor).

Call Dead Man an alternative Western, a rock Western, a psychedelic or acid Western, even an anti-Western, call it what you want. It’s certainly unusual. I saw it on its debut in Florence, Italy, where I was living at the time, and was bowled over by its quality, so much so that I sat through it again (without paying for a new ticket; will I burn in hell?)

It was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and came sixth. I would have given it the prize.

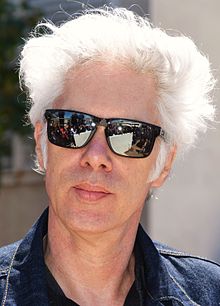

The Wikipedia entry on Jarmusch says: “Produced at a cost of almost $9 million … the film marked a significant departure for the director from his previous features. Earnest in tone in comparison to its self-consciously hip and ironic predecessors, Dead Man was thematically expansive and of an often violent and progressively more surreal character.” I’m not sure what that tells us.

The first obvious impact it has is that it’s in black & white. Jarmusch said that it gave an historic feel to the movie and that color would have been too realistic for such a mystic tale; it was also a reference to the classic Westerns of the 1940s, which he says he prefers to those of the 50s. Visually it is certainly very fine. The monochrome photography of the Arizona, Oregon, Nevada and Washington locations by Robby Müller is luminous and stark, excellent indeed. Müller is a great admirer of the work of Ansel Adams (as who is not?) and you can see the influence. In addition, there are frequent fades-to-black and scenes with no dialogue, so that it appears a series of tableaux or vignettes, heightening the early-movie impression. You almost expect caption cards.

It has been said that In the early stages of the story, when it deals with the vile and symbolically-named town of Machine and white ‘civilization’, the cinematography plays with German expressionist techniques and camera angles, while when we are in the bosom of nature and in the village of the Earth-respecting Makah people, we have a none-too Steadycam hand-held approach that recalls Italian neo-realism. I wouldn’t know about that. You might.

The second big impact, for me, was the music. The film is accompanied by a superb jangly electric-guitar score by Neil Young which I bought on CD but then found that it wasn’t at all the same on its own; it needs the visual. As a film score (it was written for the movie, Young improvising while watching the edited picture in an empty studio) it is outstanding. It is very hard to write good Western scores. You can go down the stirring Elmer Bernstein route (dum dum de-dum) as Sturges did in The Magnificent Seven and The Hallelujah Trail or the folksy Ry Coodery Long Riders road, which Walter Hill chose for that Jesse James tale, or take Robert Altman’s poetic Leonard Cohen McCabe & Mrs Miller trail. Probably best are modern orchestral variations on songs of the time, as Jeff Alexander did for Escape from Fort Bravo (Sturges again) or R Dale Butts in San Antone (Joseph Kane). Though I’m not sure if the music was always the exclusive preserve of the director; maybe not. It was in the case of Dead Man, though, no doubt about that. None of these choices is infallible. Jarmusch’s bold decision to use Neil Young rock guitar, however, works. Not everyone liked it. Roger Ebert in his review wrote that “A mood might have developed here, had it not been for the unfortunate score by Neil Young, which for the film’s final 30 minutes sounds like nothing so much as a man repeatedly dropping his guitar.” Each to his own. Still, though, Roger (may you RIP), you were wrong.

So that’s what it looks like and that’s what it sounds like. What about the actors?

There are two stunningly good performances. The classic pairing of the Western-hero white man and his Indian sidekick is turned on its head. Gary Farmer, a member of the Cayuga nation, part of the Iroquois Confederacy, is outstanding as Nobody, of mixed Blood/Blackfoot parentage, who is the wiser, more knowledgeable and stronger of the two, while Johnny Depp, in his first Western of three (well, three if you count Rango) is very far from the tough all knowing Westerner we are used to. In fact Depp is naïve to a degree, and his often vacant look, together with his absurd suit and necktie and oval eyeglasses, turn him almost into a comic character.

Almost, but not quite. There are certainly comedic episodes in Dead Man, often generated by Depp’s character’s lack of understanding and his gaucheness. So much so that Gregg Rickman has compared him to Buster Keaton. And yes, there is something quasi-Keatonish about him in this (and Depp’s John Bull topper sort of refers to Buster’s pork-pie hat). You feel that Depp might have watched Go West (1925) and imitated what the vague and inept Easterner Keaton played did there.

And yet Depp isn’t that. He’s entirely passive, as a classic Western hero, even an incompetent Easterner, never is. In a ‘journey Western’, in which normally the hero makes a psychological or moral journey as much as a physical one, Depp’s character never learns anything from his ordeal, or from his spiritual guide Nobody. As Rickman said, “he is a traveler across a mythic landscape who remains oblivious to it.” Even at the end, when we feel he might just have begun to grasp something, when Nobody tells him of his impending final journey “back where you came from”, he replies vacuously, “You mean Cleveland?” It’s funny, yes, but also bleak. He has understood nothing. Nobody often calls him the “stupid fucking white man” and you feel he has a point. More irony when you consider Depp is actually a quarter Cherokee.

I am sure Depp reflected on this role when it became his turn to play the Indian, in The Lone Ranger (2013). There, he is the canny one with the limelight on him, while the white man is the dumb straight guy.

As for Farmer, he is as far from the typical ‘Indian’ of Westerns as you could get. Even when we had more modern sympathetic portrayals of Native Americans, such as Chief Dan George in The Outlaw Josey Wales, say, it is still Clint Eastwood’s Wales who leads. Dan George is no menial Tonto but he’s still relegated to second fiddle. But in this film it is Depp who follows blindly in his leader’s path and survives (as long as he does anyway for he is a dead man, remember) only because of him – that and dumb luck, anyway. When they acquire a pack mule, it is Depp who has to tow it as he follows behind – it wouldn’t have been that way in any normal Western. But, as must be clear by now, this is far from a normal Western.

In this picture only the Indians have any spiritual quality at all. All the white men apart from Depp (who is a child in the West, Innocence in fact) are brutal, nature-hating polluters who create monstrous industrial towns, murder for money, think animals are only there to be killed, are contemptuous of their fellow men and are all, well, loathsome. In some ways Dead Man reminds me in this of the more mainstream Dances with Wolves of five years before: in that too all the white men (except Costner) were horrible while all the Native Americans were noble ecowarriors. But Farmer’s Nobody is a complex character, a philosopher, an outcast, a person, not just an ‘Indian’ or representative of a race. It is a name he has chosen, in preference to what people called him, which was Xebeche, ‘He who talks loud and says nothing.’

Farmer outstanding

The ‘Nobody’ name is of course one of the oldest jokes in the book. The Odyssey tells in Book 9 of Odysseus, when fighting the Cyclops Polyphemus, using the name Nobody (Outis), so that when Polyphemus shouted in pain to his fellow giants of the island that Nobody was trying to kill him, no one bothered to come to his rescue. The same ploy was used in the Terence Hill Western My Name is Nobody in 1973, but that was only for morons.

Depp plays William Blake. The English poet, painter and printmaker William Blake (born 1757, died 1827) is clearly a huge influence on Jarmusch. Blake’s works are liberally quoted in Dead Man, especially by Nobody, and the spirit of the poet permeates the film. Myself, I always found Blake quite difficult reading. The Wikipedia entry on him says that “Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work.” I like that Blake was so ahead of his time in abhorring slavery and believing in racial and sexual equality but I don’t care for the religious themes and imagery that feature so largely in his oeuvre and I instinctively mistrust any artist who “believed he was personally instructed and encouraged by archangels to create his artistic works”. Certainly, however, Blake wrote much about the contrast and conflict between Innocence and Experience. And it is principally this, I think, that Jarmusch takes up for Dead Man. But I find a lot of Blake (see above under middle-brow) plumb hard to understand. If not unique, I think I am in the minority, though. Blake’s admirers are legion. And Jarmusch is clearly among them.

Naturally, Depp’s William Blake has never heard of the English one. But Nobody has. The Indian was taken as a captive to England, attended schools there and read Blake. He can quote the poet by the yard. And Nobody mistakes (or recognizes?) one Blake for the other, taking upon himself the mission of guiding Blake to “the bridge made of waters” where he will be “taken up to the next level of the world – the place where William Blake is from – where his spirit belongs.” No, not Cleveland.

The most notable verse of Blake’s used in the film is from his Auguries of Innocence (c 1803):

Some to Misery are Born.

Every Morn & every Night

Some are Born to sweet delight.

.

.

William Blake, from Cleveland, Ohio, after his parents died and his sweetheart “changed her mind”, vacantly stares and occasionally snoozes his agonizingly slow way across the Great Plains and into the Rockies, to take up a new job he has been offered as an accountant in the Dickinson Metal Works of the appropriately-named town of Machine.

The journey is brilliantly shown both by the changing landscape as Blake stares through the window and by the changing passengers, from well-dressed ladies to stolid farmers to wild mountain men or buffalo hunters.

There’s also a curious interlude when the strangely interrogative fireman (Crispin Glover) sits down in front of Blake, looking like nothing so much as an actor in blackface. He says, “I’ll tell you one thing for sure… I wouldn’t trust no words written down on no piece of paper, especially from no Dickinson out in the town of Machine. You’re just as likely to find your own grave.”

There’s a town named La Machine near me here in central France. It was a thriving coal-mining place, though since the mines have shut it is not looking quite so prosperous. The Machine in Dead Man is a ghastly, squalid place dominated by the Dickinson Metal Works, what Blake might have called a dark, satanic mill. Dickinson himself, the owner of the factory, is a tyrant, played in a cameo by a splendidly malevolent Robert Mitchum in one of his last roles and his last Western. Rickman says he might be Urizen, another Blake character, an “angry, powerful near-deity … associated with smoke, flame, and metal.”

In the office of the works, once Blake has ‘entered the machine’, he is scorned and mocked – the promised job has been given to another. The office boss is a petty tyrant himself, very well played (for once) by John Hurt. Blake demands to see Dickinson but Dickinson aims a shotgun at him and sends him packing, in his “goddam clown suit.”

Out in the street of mud, populated by drunks, whores and a pissing horse, Blake is down

to pretty well his last dime, but he wants a drink. There’s quite a Buster Keaton-ish moment when he asks for a bottle in a saloon, the barman looks at the money, takes the bottle back and swaps it for a small one, very reminiscent of the opening scene of Go West.

Blake meets a girl, being mistreated by a lout. He doesn’t confront the man, out of cowardice (“I didn’t want to cause trouble”) but instead helps the fallen girl to her feet. This is Thel – a name also redolent of William Blake, for she was the title character of Blake’s The Book of Thel (1789), a spirit who witnesses how terrible the world is and cries out in horror and refusal to be an earthly woman. Jarmusch’s Thel makes a living by making and selling paper flowers. They are beautiful but have no scent. Rickman thinks the white flowers may be a reference to the cactus flowers in The Man who Shot Liberty Valance. Hmm, maybe. She is played by Mili Avital. At any rate Blake walks her home and is invited in.

There, in bed, Blake finds a gun under the pillow. “Watch it,” she warns. “It’s loaded.” He looks surprised. “Why do you have this?” he asks. “Because this is America.” They are surprised by her suitor, Charlie, the son of factory owner Dickinson, played, really well in his short part, by Gabriel Byrne. He is more puzzled and disappointed than angry, dumbly leaves the wrapped gift he had brought for her, and turns to go, but when she blurts out that she never loved him anyway, he snaps, turns and shoots. The bullet passes through her body, into the chest of Blake, lodging near his heart. It is a death wound for Thel but will also turn out to be so for Blake. He grabs Thel’s gun and shoots back, more by luck than skill hitting Charlie in the neck and killing him.

Blake makes a blundering escape on Charlie’s pinto but Dickinson père now hires three gunfighters, “killers of men and Indians” as he calls them, to find Blake and bring him in, dead or alive, “though I reckon dead would be easier”. He seems more incensed at losing the pinto than the son. The homicidal trio are a wonderful creation of the Western, the gabby Conway Twill, who sleeps with a teddy bear and just won’t shut up (Michael Wincott), an African-American boy, Johnny ‘The Kid’ Pickett, said to be 14 (Eugene Byrd, actually 20) and to have killed 14 men (perhaps a reference to Billy the Kid, who in legend was said to have killed a man for every year of his life), and the most repellent of them all, Cole Wilson (a superb Lance Henriksen, Ring Shelton in Appaloosa, Ace Hanlon in The Quick and the Dead – and by the way, I’ve only just twigged that Ace Hanlon was the name of the bad guy in Adventures of Red Ryder). Gunfighters are often given the name Cole in Westerns, in vague reference to Cole Younger (Clay, Morgan and Ringo are also popular), as I am sure Jarmusch knew. Cole will eventually be so incensed by the garrulous Twill that he will have a bone to pick with him.

The rest of the story tells of Nobody finding the “stupid fucking white man”, being astonished at his name, and accompanying him through a series of adventures, or rather misadventures,

trying to avoid the pursuit of the three gunmen, as well as the official law in the shape of twin US marshals (Mark Bringelson and Jimmie Ray Weeks). The marshals do not fare well. We see the head of one in the equally dead fire, the unburnt sticks like the halo on an icon. Cole Wilson comes up and crushes the skull, in an especially grisly bit. In fact there is a leitmotif of the skull running all through the movie. Bones and hides and especially skulls litter the film. Dickinson had a skull on his desk.

Jarmusch calls these two marshals Lee and Marvin, and why should he not be allowed his jokes? (Jarmusch is a founding member of The Sons of Lee Marvin, a “semi-secret society” of artists resembling the iconic actor, which issues communiqués and meets on occasion for the ostensible purpose of watching Marvin’s films). He also calls Billy Bob Thornton’s character Big George Drakoulious. George Drakoulious (you will know this) has produced music for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Jared Harris’s character is named Benmont Tench. The fine Benmont Tench, a great solo artist too, was also a member of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. And since we are on the subject, the late great Tom Petty (we miss you so much, Tom) tended to wear a John Bull low-crowned topper too. Jarmusch is of course himself a rock (or something) musician. And Gary Farmer has a blues band, called Gary Farmer and the Troublemakers. Troublemakers, Heartbreakers, hey.

But where were we?

There are a number of blackly funny and/or creepy episodes as Nobody and Blake meet various unsavory characters, such as Alfred Molina as a disgusting storekeeper/missionary who sells blankets infected with small pox to the Indians,

and a trio of travelers, including Billy Bob Thornton and Iggy Pop in a dress, who contemplate a homosexual rape of Blake and argue over him (“I saw him first!”) – they think he is alone because he says he is traveling with Nobody. Meanwhile, Cole Wilson is indulging in a habit the Cyclops was fond of too.

There’s a running gag about tobacco.

There is another interesting idea, that of the mirror. The film is symmetrical in many ways: perhaps an attempt at Blakes’s “fearful symmetry”. Early on, as Depp walked down that muddy main street of Machine, a man pointed a pistol at him and would fire bullets into his body as soon as not. Blake is alive and they would kill him. Towards the end of the film he walks down another main street, this time the thoroughfare of the Makah village. This too is muddy and untidy but is populated by caring people who help him die with dignity. The Indians, especially Nobody, do not teach him the Indian way of life. They show him the Indian way of death. And such man-made artifacts as are here in this street are beautiful hand-carved totem poles; metal devices are scorned, such as the sewing machine lying abandoned in the mud. He is dead and they help him ‘live’. Blake and Nobody are also twinned and have much in common. They meet their death at the same time. They are both outcasts and outlaws. They are both pursued by hired killers. Nobody calls the ocean upon which he sends Blake out on his final journey “the mirror of water.”

As they get farther from ‘civilization’ (i.e. squalor), leaving white men behind, and nearer to the home of the people who will help Nobody and Blake – real Native Americans, exotic like Eskimos or Hawaians or something, not Hollywood ‘Indians’ in any way – the landscape improves, seems healthier, cleaner. They even spot a live animal, an elk, at which Nobody smiles. (Among the final credits is ‘Elk wrangler’).

The brief episodes followed by fades-to-black seem now to reflect Blake’s slipping in and out of consciousness.

The ending is final in many ways.

If you don’t like Dead Man, you may take solace in the fact that you are not alone. Roger Ebert aid, “Dead Man is a strange, slow, unrewarding movie that provides us with more time to think about its meaning than with meaning.” He Added, “Jim Jarmusch is trying to get at something here, and I don’t have a clue what it is.” (Sounds like me and Blake).

Stephen Holden in The New York Times wrote, “The film’s energy begins to flag after less than an hour, and as its pulse slackens it turns into a quirky allegory, punctuated with brilliant visionary flashes that partially redeem a philosophic ham-handedness. Audiences attuned to Jarmusch’s drolly hip sensibility should be delighted with the film, but to the uninitiated, its drier patches are just as likely to induce yawns.”

Edward Guthmann in The San Francisco Chronicle said, “Jarmusch tries a lot of other effects — some amusing, some grotesque — and gets so caught up in stylistic touches and loopy humor that he never finishes the statement he started to make about the fragility of our lives and identities, and how vulnerable we are when removed from the comforts and social constructs that usually surround us.”

These critics didn’t get it, or maybe I should say didn’t dig it at all. I dug it a lot. Dead Man is an extremely good Western, outstanding, in fact: unusual, post-revisionist, I’d say, very 1990s, horribly realistic (especially the shootings), occasionally plain odd, possibly pretentious here and there but I don’t think so, in any case incredibly well acted, written and directed and with a great deal to say.

See, you really can say something original and new with a well-worn genre.

If you are Depp, Farmer and Jarmusch anyway.

I think I’ve gone on too long again. Sorry about that. I need a ruthless editor. Still, it’s shorter than Gregg Rickman’s essay.

7 Responses

Dead Man is a strange film in that I find I like it less every time I watch it, although it's still interesting and mostly enjoyable. I find it incredibly pretentious though and the in-jokes are annoying. I also think Jarmusch is an unscrupulous character. In the late 80s he was supposed to direct a Western written by Rudy Wurlitzer (writer of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid) called Zebulon. Zebulon was about a mountain man who got a bullet embedded in his heart and is referred to as a "dead man" by his Indian friend as he goes on an episodic journey encountering various characters in the American West until he goes to the spirit world. Outside of the mountain man element does that sound familiar? After they had some creative differences, Jarmusch cannibalized Wurlitzer's script and used it for the creation of Dead Man, essentially ensuring that Zebulon could never get made in its current form and not giving Wurlitzer an ounce of credit. Director Alex Cox tried to persuade Wurlitzer to take legal action but Wurlitzer had become something of a passive Buddhist and let it go, rewriting his script into the novel The Drop Edge of Yonder. This is not the first time Jarmusch has been accused of outright theft (see Broken Flowers). Having read Zebulon it has a far superior script to Dead Man. More sad and elegaic like Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Dead Man can't help but pale in comparison.

Fascinating. Thanks, David.

Yes, David, very interesting. Thank you. I didn't know any of that.

Of course if Jarmusch was guilty of plagiarism (I say if: doubtless the lawyers would have argued it back and forth and made lots of money) it wouldn't have been the first or last time the script for a Western was 'appropriated'. One thinks of John Wayne pitching his Alamo idea to Republic in the 50s, studio boss Herb Yates turning it down because of the huge budget, then doing it himself on the cheap. Wayne was furious and never spoke to him again. Ironically, though, whatever the moral rights and wrongs, THE LAST COMMAND turned out a better picture than THE ALAMO. No great film, certainly, THE LAST COMMAND was a perky actioner, while THE ALAMO was a huge, bloated mess.

I am sure there have been many other script ideas 'borrowed' to make Westerns. Kind of dog-eat-dog in Hollywood, I guess.

Jeff

NOT DO-EAT-DOG. The Alamo is and was an historical event. No one had dibs on it. As you wrote, The Last Command a much better film; I love Wayne, but hated his Alamo.

Jeff, another good write-up of a head-scratcher of a Western Movie. I can't believe you rated it 5 pistols. Although, you stated your points very well, in defense of your 5 pistol rating. That said, I still can't see Jim Jarmusch's nihilistic DEAD MAN(filmed 1994, released 1995) as a 5 pistol. It doesn't have a single derringer in it, although William Blake(Johnny Depp) holds a neat Colt 1849 .31 caliber 4" barrel pocket pistol at the end of the movie.

With the above said, I do like some particulars of this weird fantasy Western. Nobody(Gary Farmer) isn't portrayed has a stereotyped Indian sidekick, which is enlightening, to say the least. The atmospheric black and white photography of Robby Muller, makes the movie look like 1870's photographs. The period costuming and wardrobe is spot on thanks to Marit Allen, who also did a great job on RIDE WITH THE DEVIL(filmed 1998, released 1999). Kudos to Bob Ziembicki production designer, set decorator Dayna Lee, and Ted Berner art direction. Also, the weaponry was detailed authentic for the late 1870's period. They got it right. In my opinion it is 5 pistols in production authentic detail.

I just can't get into the story, or Jarmusch's agenda concerning capitalism and industrialization. Also, some of the crassness I could do without, although I'm not prudish. I agree with David Lambert that DEAD MAN is still interesting and mostly enjoyable, but I would rather watch BLOOD ON THE MOON(1948), or THE BIG SKY(filmed 1951, released 1952).

According to David Lambert Jarmusch did a Cole Wilson(Lance Henriksen) on Rudy Wurlitzer's original screenplay BEYOND THE MOUNTAIN, which Wurlitzer wrote in the late 1970's and was circulating in the 1980's under the renamed title ZEBULON. Sam Peckinpah, Hal Ashby, Roger Spottiswoode, Alex Cox, as well as Jim Jarmusch were all interested in making the movie at one time or another, but it remained an unproduced screenplay. That is, until Jarmusch creatively lifted from Wurlitzer's script and got the movie made. In all probability(but who am I, to know for sure) the movie would never have been made, if it hadn't been for Jim Jarmusch. In my opinion Jarmusch should have given Rudy Wurlitzer credit, but he didn't.

Rudy Wurlitzer's novel THE DROP EDGE OF YONDER, based on his script, was published in 2008.

I’m also on the admiration side of the fence Jeff, largely because of Farmer’s wonderful characterization. A comment about your pistol ratings. Where are they? I read other comments from people who mention them, but I can’t seem to find them anywhere. For instance – at the top of your critique of this film there is the date of posting, # of comments and labels: uncategorized and nothing at the end except for previous film reviewed and next one and then responses from others.

I agree with you about this haunting film. I could not believe that Criterion put out a deluxe edition of it. I snapped it right up and its a tremendous presentation.