Clay Allison shot to death, again

The third feature Western (that I know of) to feature the disreputable Western character Clay Allison (click the link for our essay on him) was a humble PRC oater of 1945. We’ve already had a look at Paramount’s Hopalong Cassidy picture in 1938 and Republic’s Three Mesquiteers one in 1939, so click the links if you want to know more about Allison in those.

Fighting Bill Carson had in common with the first two that they used the figure of Allison as the chief villain, without making any attempt to portray the real one. It was just a convenient name which signaled ‘bad guy’.

This Allison was played by I Stanford Jolley (as Stan Jolley). As the IMDb bio of him says, “Perennial film western heavy I. Stanford Jolley could be spotted anywhere and everywhere in dusty ‘B’ fare from 1935 on. Often mustachioed, this freelancing, wideset-eyed, black-hatted villain, who showed up in Hollywood following vaudeville and Broadway experience, could be counted on to give the sagebrush hero a devil of a time before the film’s end.”

His Allison, like the other two, wears a suit and seems at first a goody, perfectly charming and all, but, 12 minutes into this version, he is revealed to be the chief crook. We already knew that though because we saw him coming into town on the stage in the first reel and he had a thin mustache and was wearing a frock coat, so clearly was a wrong ‘un.

The Paramount and Republic films had hardly been big-budget affairs, au contraire, but they were mega-blockbusters compared with Fighting Bill Carson. It was shot in a matter of a few days on the Corriganville Ranch, and it had a small cast, cheap-looking sets and a runtime of just 53 minutes.

It was made by the Neufeld brothers – producer Sigmund Neufeld and director Sam Newfield (he anglicized his name). It was strictly formulaic, following the B-Western conventions as closely as a Noh play or a D’Oyly Carte Gilbert and Sullivan operetta.

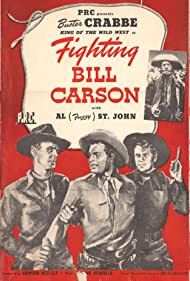

It starred Buster Crabbe and Al Fuzzy St John. Buster had taken over from Bob Steele as Billy the Kid in the long series of Billy programmers and did thirteen of them before pressure on PRC not to glorify an outlaw made them change Billy’s name mid-1943 to Billy Carson. He then did 23 more as Carson; this was the sixteenth. What on earth the studio felt the pressure was is a mystery because their Billy the Kid, be he Bob or Buster, was nothing but a Western knight in figurative shining armor, roamin’ the West and doing good to all. Perish the thought that he would actually do any outlawin’. They usually used the old excuse that other people were committing crimes and putting the blame on the entirely innocent Billy. Still, he was Billy Carson now.

In this one, Fuzzy is owner of the general store in Eureka who complains to the local sheriff (good old Bud Osborne) that there ain’t no bank, and how can a businessman prosper without a bank? It seems that banks are illegal in Texas. I didn’t know that. I learn, though, from a History of the Banking Industry in Texas and the Department (my favorite bedtime reading) that:

In 1845, the first Constitution of the State of Texas provided that “[n]o corporate body shall hereafter be created, renewed, or extended, with banking or discounting privileges,” and this prohibition against the chartering of banks was carried forward into the Constitutions of 1861 and 1866, deleted in the Constitution of 1869, and added back into the present-day Constitution of 1876 as Article XVI, Section 16. Banking certainly existed during these periods but was dominated by private, unincorporated banks, many of which issued their own currency. In 1865, the first national bank in Texas was organized in Galveston.

During the period 1869-1876, a number of state-chartered banks were created by special acts of the Legislature. Ten additional state banks were established under a general law passed in 1874. Only a few of these banks ever actually opened for business. From 1876 to 1900, banking in Texas was conducted by private banks, existing state banks, and national banks. As of 1890, 148 private banks were operating in Texas.

Who knew? It rather sabotages all those bank-robbery Westerns set in Texas. Never mind.

However, in this thriller local rancher Clay Allison goes to the Capitol and gets the legislature to legalize all banks. He himself declines the offer of becoming president of the new bank in Eureka and nominates Fuzzy in his stead. Naturally, he has a cunning plan to get all the local farmers and ranchers to put their money in this one place, then rob it.

He has a glam niece, Jean (Kay Hughes, again according to IMDb, a “B-level actress [who] was one of the more wholesomely attractive, if minor, co-stars of westerns, crimers and serials of the late 30s.” She gets a job in the new bank and craftily gets to know the combination of the safe and tell her wicked uncle.

So you see the plot, such as it was, thickens. This plot came from the pen (or typewriter) of Louise Rousseau, credited with both story and screenplay. Louise was a regular Jimmy Wakely writer.

The budget could only stand two henchmen for Allison but nice to see that one of them, Henchman Cass, is our old pal Kermit Maynard, Ken’s bro, a stuntman and stand-in who got to lead in his own oaters for a time before descending to character parts in Poverty Row oaters.

Squeezed into the modest runtime are all the usual tropes, stagecoach holdup, fisticuffs, horse chases, bushwhackin’, bank robbery and so on, still leaving time for some comic shtick from Fuzzy. Why is it, I’d like to know, that the bandits always wait till the stage has gone past before they gallop after it? Wouldn’t it be more sensible to waylay it, blocking its path? And why do they always shoot their six-guns into the air while chasing the coach? And how do they always hit the driver, with a Colt .45 at three hundred yards from the back of a galloping horse?

Anyway, that’s the third time that Clay Allison has been shot to death in the final reel. I thought he broke his neck in a wagon accident in 1887, but apparently not.

That was the last big-screen Western (that I know of) to feature Clay Allison. He did, however figure in a TV show or two. But more of that another day.