.

An absolute gem

For the last two Westerns of the seven-picture cycle that Budd Boetticher made with Randolph Scott in the late 1950s, Ride Lonesome and Comanche Station, it was back to the ‘pure’ line-up: the Columbia lady to hold aloft her torch – even if studio boss Harry Cohn was no more, a heart attack having put paid to him in February 1958 – Burt Kennedy to write, Charles Lawton Jr at the camera, Lone Pine locations for him to photograph, Harry Joe Brown to produce – with Scott, and Boetticher too this time; in fact Brown was rarely on the set, being slightly persona non grata with the new post-Cohn Columbia management.

No more Warner Brothers, no more iffy scripts, no more ‘town’ Westerns. Ride Lonesome gave us a plot based on a hard man out for revenge, a charming villain with saving graces, and stunningly good cinematography. This one was the first in CinemaScope, and Boetticher and Lawton used it highlight the isolation of the characters in the truly wild West, creating a lot of ‘dead space’ in order to make the characters even more ‘lonesome’.

Martin Scorsese points out that the ‘loner’ has been a theme running through all great American fiction, from Moby Dick to Taxi Driver, and is an essential element of the Western myth.

There are, once more, few personalities but clever interaction, and, naturally, a glam blonde in the mix.

I’d better say early on that IMHO, much as I like the other pictures, Ride Lonesome is the very best. Of course that’s a personal point of view and I can hear lovers of Seven Men from Now or The Tall T crying; “Mais non!” That’s fine. I admire those pictures too. But for me there is nothing wrong with Ride Lonesome. It’s tight, taut and tense, and as close to the ideal Western as you can probably get. Short, simple, powerful, it sticks in the memory. It’s sheer quality.

The title grabs me right away. What could be more ‘Western’ than a lone rider, in tough terrain, on a mission, beset by danger – Indians and bad guys? Boetticher said he wasn’t interested in big ‘conquering the West’ themes; he wasn’t even interested in communities (Sundown, Agrytown and Julesberg notwithstanding); he cared about a tough man in a tough spot, and what he did about it. Boetticher also loved horses all his life. He delighted in filming a lone rider in a truly Western setting.

Scott, who never seemed as William S Hart-like as now, in this one is Ben Brigade, a scarred, hard man out for revenge for a murdered wife. Randy seems to have got through the wives at a rate of knots.

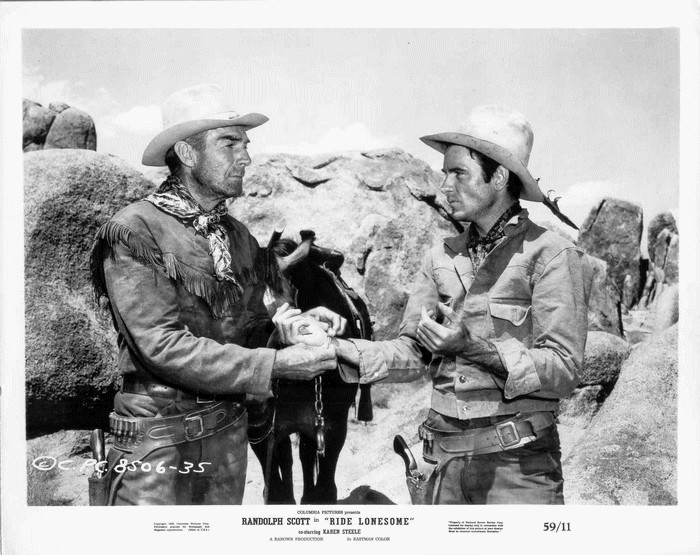

Scott is once more splendid. All the smiley happy-go-lucky side to his character evident in Buchanan Rides Alone has gone. He is once again a stoical hard-as-nails type out for vengeance. And Randy seemed to be enjoying it more. Grim-faced, taciturn, implacable, it was his kind of role.

He’s become a bounty hunter. Though a standard type in Westerns, the bounty hunter is hard to get right. He is after all a mercenary, hunting down men for money. A priori, that’s a bit of a turn-off. But Hollywood had a way of ‘sanitizing’ the job, on the big screen and small. People look askance at Henry Fonda when he rides in with a corpse to collect the bounty in the first reel of The Tin Star but he turns out to be the hero of the tale. Steve McQueen in Wanted: Dead or Alive gave his bounty away to worthy widows so often you wonder he made a living. Ultra-goodies like Audie Murphy had been bounty hunters and even Randy himself had made The Bounty Hunter at Warners in 1954 in which he was Jim Kipp, a ruthless hunter-down of wanted men who, in the classic Western way, shoots a fugitive in the rocks in the opening scenes, brings the body in flung over the man’s own horse and dumps it at the sheriff’s office, demanding the $500 reward. Of course he turns out to be not as bad as first appears. He is Randolph Scott, after all. And so it is in Ride Lonesome.

He captures outlaw Billy John and plans to take him back to Santa Cruz, California. But Brigade has a secret motive in mind, as Billy John will discover. And it isn’t the reward… Billy John is played by the excellent James Best, who, though young, already had a decade of Western features behind him. I’m sure you remember him as a Dalton in Kansas Raiders (1950) or again a Dalton, this time part of the Doolin gang, in The Cimarron Kid (another Boetticher oater), or maybe as one of The Last of the Badmen in 1957. Ride Lonesome was already his seventeenth – not to mention all the Western TV shows.

But he’s not the chief villain, of course. He fulfills the punk-kid role that Skip Homeier usually took (and had taken in The Tall T). Kennedy had given us splendid principal villains in the first two pictures, Lee Marvin’s Bill Masters and Richard Boone’s Frank Usher. These were charming-rogue bad guys, almost sympathetic, witty, clever, and they sort-of moved towards the Good as the story progressed. Pernell Roberts, just before he became Adam on the Ponderosa, was a worthy successor. His Sam Boone (I don’t think he can have been named for Richard) oozes sex-appeal (these movies contained some quite daring sexual innuendo for the time) and is, like Marvin and Boone, a complex character, talkative to Scott’s stoic silence and clearly pondering on the rightness or otherwise of his actions. It’s a very well-written role and Roberts does it impressively.

Roberts’s sidekick Whit is James Coburn, excellent in his first big role, as a country bumpkin. The added scene, to build up Coburn’s contribution a bit, where Roberts makes him a partner is really good. Boone and Whit are after Billy John too – of course for the money, but more importantly for an amnesty for former crimes that will result. So another uneasy alliance is formed. Actually, this time Scott actually seems to like Boone and Whit; with other villains, such as Lee Marvin, Richard Boone, and, in the last movie, Claude Akins, he fears and respects his foes, and is semi-drawn to them, but doesn’t actually like them.

So, bounty hunter, captured outlaw and two dubious types form a male quartet and, in classic Western style, the disunited group of whites will come under external threat from Indians.

The foursome becomes a quintet when Karen Steele joins the group. She is a widow, Mrs Lane, and Hondo-lovers will recognize that name. In fact, as Robert Nott points out in his survey The Films of Randolph Scott, this was not the only Wayne-reference in the picture and Kennedy and Boetticher seem to have had fun slyly inserting others, as a kind of affectionate dig at Duke. There’s a reference to the town of Rio Bravo (Rio Bravo had been filmed earlier that summer), the Indians ride in a similar formation to those in The Searchers, and at one point Randy adopts the arm-across-the-torso pose Wayne borrowed from Harry Carey and made famous. Scott even Wayneishly delivers the line “That tears it.”

I think that Mr Nott may have watched too many Westerns but (a) so have I and (b) that’s impossible.

Karen wears a very pointy Jane Russell-style bra and has rather 1950s more than 1870s blonde coiffure. Boetticher (still her lover) enjoys highlighting her (admittedly spectacular) figure against the skyline. Boetticher women were not, I fear, chosen for their contribution to the storyline so much as being objects – objects of desire, mostly. Steele doesn’t do too badly, though I don’t think she was much danger of winning an Oscar. Still, she holds her own, toting a rifle and riding hard. She’s no weak character.

Kennedy recycled the line “There are some things a man can’t ride around” (his version of a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do) from The Tall T, only that time it was Randolph Scott who said it, while this time it’s Pernell Roberts. Actually, as a matter of interest (for it is a matter of interest to Westernistas) at the turn of the decade there was a project for another, eighth Boetticher/Scott Western, Six Black Horses, but Scott had retired and Boetticher had self-imploded (see index for our essay on him). Harry Keller took it on. He first wanted Richard Widmark for the lead (character name: Ben Lane) but in the end Audie Murphy made it, at Universal in 1962. The whole picture has a definite Boetticher/Kennedy vibe: few characters, desert terrain, searching for someone, beset by danger, glam blonde. And wouldn’t you know it, at one point Audie tells us, yup, “There are some things a man just can’t ride around.”

It turns out that there’s a real villain, more villainous than the others, in the shape of Lee Van Cleef – though even he is allowed to be semi-likable and vaguely ashamed of himself. Actually, his part is quite small and restricted to the last reel. Boetticher liked Van Cleef but said, “He drank a lot. There were a couple of scenes in the picture where he opened his mouth and his tongue was absolutely white from the liquor, so we had to cut them out.” I think he meant the scenes, not the tongue.

You see, Brigade’s wife was kidnapped by Van Cleef as a payback for Brigade sending him to prison (Brigade used to be a lawman) and the innocent woman was brutally hanged from a cross-like hanging tree. But we only discover this towards the end and maybe I shouldn’t have told you that (and translated film titles such as L’Albero della Vendetta did the movie no service).

Only four days before Ride Lonesome was released by Columbia, Gary Cooper had barely escaped such a fate when a similar gibbet featured in Delmer Daves’s last (and very fine) Western, Warners’ The Hanging Tree. The writers, directors and producers of these movies probably didn’t make the link. But we do.

The suspense mounts. The plot unravels piece by piece, but it’s ‘linear’, without twists this time. You could even say it’s slow-moving, but not in any bad way. It slowly builds tension. Brigade wants to go slowly, deliberately, and there’s quite a clever inversion of the usual race-against-time scenario. The characters learn from each other. Then there is a stunning, climactic ending. The tree is an unforgettable image. And there’s no blood bath: justice seems to prevail over vengeance. In the last resort, despite the grimness, it seems to me an optimistic Western.

The picture was released in February 1959. Once again, it was received moderately. The mainstream press had rather given up reviewing what it regarded as ‘B-Westerns’. The box-office returns were disappointing, though again it made money finally by being highly popular in Europe, and it has since very much ‘grown’ in stature. In The Rough Guide to Westerns Paul Simpson says that Boetticher “achieved perfection here”.

It was Burt Kennedy’s second-favorite after Seven Men from Now. Robert Nott says, “Ride Lonesome is a little beauty of a Western” and he is right. That little is not meant in any demeaning way. The picture is small in terms of runtime, limited cast and scope, if you like, but then so are diamonds small.

Two months after the première of Ride Lonesome, Warners released Westbound, which had been made in the fall of 1957 but held back. In the summer of ’59 the ‘proper’ team got together again to make what would turn out to be the last in the cycle, Comanche Station, and we shall finish our overview of these Boetticher/Scott Westerns with that one, next time. So until then, hasta la vista, compadres.

One Response

This movie is marvelous. Everybody is great in this. Scott awesome and Pernell Roberts with James Coburn really help make the movie. Truly in the front rank of Westerns. Excellent review.