The Silver Fox

Jeff Arnold’s West has looked at the Western careers of some of the greatest film directors, artists such as Francis Ford, John Ford, Henry Hathaay, Delmer Daves, Anthony Mann and Sam Peckinpah. Others will follow. Today it’s the turn of Howard Hawks.

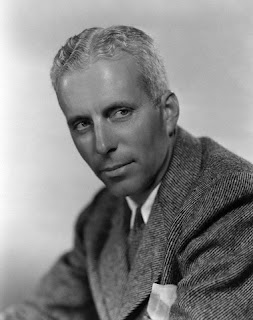

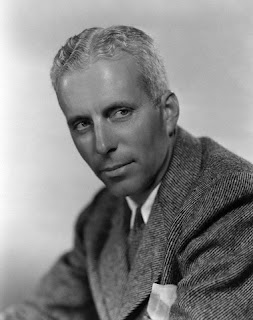

Hawks (left) was perhaps the greatest Hollywood director never to win a Best Director Oscar (though he was given a consolatory honorary award in 1975 – by John Wayne). His friend and admirer John Ford generously suggested that he should have been recognized as best director, instead of Ford, for Sergeant York in 1941. Sergeant York was a fine film but it was perhaps Hawks’s bad luck that it came out the same year as Ford’s magnificent The Grapes of Wrath. For me, though, Hawks should have been a contender for Best Director for his 1948 picture Red River, a splendid film and one of the finest Westerns ever made. He wasn’t even nominated (Elia Kazan won it for Gentleman’s Agreement).

Hawks (left) was perhaps the greatest Hollywood director never to win a Best Director Oscar (though he was given a consolatory honorary award in 1975 – by John Wayne). His friend and admirer John Ford generously suggested that he should have been recognized as best director, instead of Ford, for Sergeant York in 1941. Sergeant York was a fine film but it was perhaps Hawks’s bad luck that it came out the same year as Ford’s magnificent The Grapes of Wrath. For me, though, Hawks should have been a contender for Best Director for his 1948 picture Red River, a splendid film and one of the finest Westerns ever made. He wasn’t even nominated (Elia Kazan won it for Gentleman’s Agreement).

Hawks had an attractively no-nonsense style. His own definition of what makes a good movie was, “Three great scenes, no bad ones.” He also defined a good director as “someone who doesn’t annoy you.” This minimalist approach was sound and unpretentious. The Cahiers du Cinéma enthusiasts in France intellectualized his films in a way which amused him greatly. His Westerns were actioners. He said, “There’s action only if there’s danger.”

.

.

They got on

.

He really liked and esteemed John Wayne and made four of his six Westerns (the six that can be properly attributed to him) with Duke. He said, “John Wayne represents more force, more power, than anybody else on the screen”, adding that Duke “is underrated. He’s an awfully good actor. He holds a thing together; he gives it a solidity and honesty, and he can make a lot of things believable.” He also said, “When [John Ford] was dying, we used to discuss how tough it was to make a good Western without [Wayne].” Hawks had a similar affection and respect for Walter Brennan.

Hawks was also good with women, unlike Ford. His female characters are often ‘just one of the guys’, as it were, and the term Hawksian Women has been used since. Joanne Dru’s Tess in Red River is a good example, or Angie Dickinson’s Feathers in Rio Bravo.

Early days

Howard Hawks’s love of the Western started early. He edited Paramount’s 1924 silent version of The Heritage of the Desert with Noah Beery and later the same year he was a production manager

(uncredited) on the studio’s Jack Holt oater North of 36. The following year he was production manager on two more silent Zane Grey pictures, The Light of Western Stars, with both Holt and Beery, and The Code of the West. So he was learning the Western in his twenties.

In 1932 Hawks made it big by directing the talkie Scarface for producer Howard Hughes. Hawks’s first job helming a Western, though, was when he directed part of MGM’s Viva Villa! (1934) with Wallace Beery as Pancho Villa. It was quite a scandal: in November 1933, during location filming in Mexico, actor Lee Tracy is said to have got drunk and urinated from his hotel balcony onto a passing military parade. Tracy was arrested, fired from the film and replaced by Stuart Erwin, and Howard Hawks was also let go as director for refusing to testify against Tracy, and was replaced by Jack Conway, the credited director. However, in his autobiography, Charles G Clarke, the cinematographer on the picture, said that the incident never happened. Tracy, he said, was standing on the balcony watching the parade when a Mexican in the street below made an obscene gesture at him. Tracy replied in kind, and the next day a local newspaper printed a story that said, in effect, Tracy had insulted Mexicans, Mexico and the Mexican flag. The story caused an uproar in the country, and MGM decided to sacrifice Tracy and Hawks in order to be allowed to continue filming there. It was not an auspicious start to Hawks’s Western-directing career…

.

.

Actually a fine movie, tho’ Hawks’s input was minimal

.

Hawks was, however, credited director on the Samuel Goldwyn production Barbary Coast, released by United Artists, the following year. It’s a melodramatic tale of crime in California starring Edward G Robinson and Miriam Hopkins (who couldn’t stand each other) with a young Joel McCrea as ingénu – and Brennan as old-timer. Hawks did a good job of creating an almost Dickensian fog-bound waterfront but much of the acting left something to be desired. William Wyler is said to have directed certain scenes.

.

.

Good cast!

.

The Outlaw

There was then a Western pause in Hawks’s career while he concentrated on other genres (he was one of Hollywood’s most versatile directors) and he next pops up in the West on the hilariously bad Billy the Kid picture The Outlaw, shot at the turn of the decade but not released till 1943. Hawks is also said to have written quite a lot of it.

However, it wasn’t entirely Hawks’s fault that the picture was dire: it was another Howard Hughes production and Hughes fired Hawks after only two weeks, taking over himself, so it was Hughes who was responsible for the salacious and lurid aspects of it. It all seems very tame to us today but at the time it was hyped as a sex drama and busty Jane Russell dominated the posters (often Jack Buetel, as the title Billy, didn’t even feature). The acting was excruciating, especially Thomas Mitchell as a ludicrous Pat Garrett, the very weak Buetel and an absurdly miscast Walter Huston as Doc

Holliday (don’t ask what Doc Holliday was doing in a Billy picture).

.

.

Trashy

.

So far, it must be said, Howard Hawks’s Western career was not exactly stellar…

Red River

But all that was put behind him when in 1948 Red River was finally released. It was filmed back in ’46 but there were many delays. Hawks wanted endless editing and there was also an absurd claim by Howard Hughes that the picture was similar to The Outlaw (it was nothing like it; for one thing, Red River was good). If anything, the plot was a Western Mutiny on the Bounty, as writer Borden Chase admitted. In any case, the picture wasn’t released until August 1948, after John Ford’s Fort Apache, shot afterwards, in late ‘47.

.

.

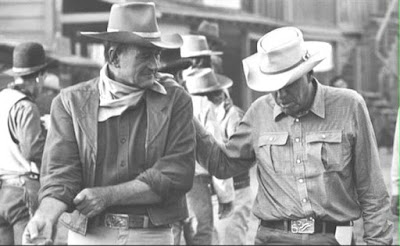

Friend and colleague – and slight rival – John Ford

.

Ford does seem to have had some input to Red River. Tag Gallagher, in his book John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press, 1984), suggests that Ford assisted Hawks on the set and made numerous editing suggestions, including the use of a narrator. It may have been so. Certainly Ford wrote to Hawks asking him to “take care of my boy Duke” (John Wayne was of course starring for Hawks). Hawks did say that he often thought of Ford when shooting, particularly in a burial scene when ominous clouds started to gather. Hawks told Ford, “Hey, I’ve got one almost as good as you can do – you better go and see it.”

Wayne is supremely good in Red River, playing the alpha-male Thomas Dunson who founds a cattle empire but as he ages he has to face the rebellion of his adopted son Matt Garth (Montgomery Clift in his debut). As Wayne would do for Ford in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, he played an older man with great skill. The role was first offered to Gary Cooper but he turned it down because the ruthlessness of the character wouldn’t suit his screen image.

.

.

Duke magnificent in Red River

.

Visually, the film is stunning. Hawks had first wanted the great Gregg Toland as cinematographer but Hawks and Russell Harlan did a superb job, shooting the splendid Arizona locations in a glowing black & white.

The movie was the third biggest grossing film of the year (fortunately, because budgeted at half a million dollars, it cost more than double that) and is nowadays, justly, ranked #5 on the American Film Institute’s list of the greatest Westerns of all time.

The Big Sky

There’s no doubt that Red River was Howard Hawks’s greatest Western but his next, The Big Sky, (RKO, 1952), was also a big production, and popular, though not such a biog grosser. Based on the famous novel by AB Guthrie Jr, it was the last of three pictures written for Hawks by Dudley Nichols, one of John Ford’s regulars, and it is an early Western, telling of trappers and fur traders and their conflict with Indians in the 1830s. Hawks first wanted Marlon Brando for the lead part of Jim Deakins but Brando wanted too much money and the director got Kirk Douglas, who had debuted in a Western rather tentatively the year before in the Raoul Walsh-directed Along the Great Divide and had, rather unwillingly, done another Western-ish picture earlier the same year as the Hawks movie, The Big Trees, directed by Felix Feist. Douglas was far from a big Western star at the time. He brought energy to the part, though. He was in any case better than Brando would have been; Brando was hopeless in Westerns.

.

.

Not that big

.

The Big Sky is not a superb Western, it is fair to say, and it is slow in parts. At 140 minutes originally it was too ponderous and it was cut on re-release to a more manageable length. But it is beautifully photographed – once more by Russell Harlan in black and white – and some of the support acting is terrific, notably Oscar-nominated Arthur Hunnicutt, who also narrates.

At any rate, Hawks now had two big Westerns to his name and was established as one of the genre’s important directors.

Rio Bravo

At the end of the 50s Hawks came out with another big, commercial Western, this time in color, Warner Brothers’ Rio Bravo. It was back to John Wayne. In 1959 Duke was rather preoccupied with setting up his own mega-project, The Alamo, but he found time to do a Western for Hawks and one (The Horse Soldiers) for Ford.

Rio Bravo is great fun. Quentin Tarantino has said that if he started getting interested in a girl he would show her Rio Bravo. And she better like it… There is little Fordian artistry about it. Though directed by Hawks and co-starring Walter Brennan, it was no Red River either. It was a classic, commercial Western of straightforward design, and it was a box-office blast. It had them waiting in lines all round the block to get in. Hawks once said, “If you want to make pictures and enjoy making them, you better go out and make something that a lot of people want to see.” He sure got it right this time.

.

.

Cast and crew

.

Wayne is his usual leathery self, spinning his Winchester to cock it. I love his short jacket and calf-length pants and that hat has to be one of the best ever (Wayne had worn it since Stagecoach).

It’s a hugely enjoyable film, full of color and corn, and none the worse for that. It has a splendid final shoot out. It’s juvenile, predictable and full of clichés but it’s a real Western with zip and pzazz and you have to love it. High Noon it ain’t but they can’t all be works of art with political messages. Hawks said, “I never made a message picture, and I hope I never do.” He didn’t even like High Noon. “I didn’t think a good sheriff was going to go running around town like a chicken with his head off asking for help, and finally his Quaker wife had to save him. That isn’t my idea of a good western sheriff.” In fact, Rio Bravo was a kind of riposte to High Noon. Wayne had also disliked the Gary Cooper picture, in which the marshal had thrown the sheriff’s star in the dirt. It was un-American, he thought. Law ‘n’ order must be respected. In his version, the sheriff obstinately retains his badge and wins out over the bad guys against all the odds, this time with the help some townspeople, but essentially by his own bravado and by bossing his minions around.

This was the late 50s and early 60s when no Western was complete without a pop singer. Ricky Nelson looks about 12 though he was 18. He can’t sing worth a damn compared to Dean Martin but they make a decent duo with ‘My rifle, pony and me’ (the tune was used in Red River), with Walter Brennan’s harmonica obligato. Luckily Wayne (‘Singin’ Sandy’, remember?) didn’t have to join in.

The auteuriste Europeans read huge amounts into Rio Bravo, which made Hawks laugh. Jean-Luc Godard wrote, “The great filmmakers always tie themselves down by complying with the rules of the game. … Take, for example, the films of Howard Hawks, and in particular Rio Bravo. That is a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception, but Hawks has made his film so that the insight can pass unnoticed without disturbing the audience that has come to see a Western like all the others.” Well, he could be right, I guess. Oh look, there goes a flying pig.

El Dorado

Hawks made two more Westerns, at the tail-end of the 60s. In fact his last ever movies were Westerns. They weren’t quite as good as the previous ones but are still more than watchable. El Dorado in 1969 was pretty well a remake of Rio Bravo, but this time for Paramount. Wayne was back, so that sold tickets, but it had less of the charm of the previous movie. This time Robert Mitchum took the Dean Martin part of alcoholic deputy and the Ricky Nelson role was taken by a young James Caan. And, back from the The Big Sky, Arthur Hunnicutt takes Brennan’s crusty old-timer part.

.

.

In the chair

.

Mercifully, they cut out the jailhouse scene where, copying Dino/Brennan in Rio Bravo, Mitchum sings accompanied by Hunnicutt on harmonica. It was because Hawks’s son said, “A sheriff shouldn’t sing.” Astute.

The opening credits feature a series of nice original Remingtonesque paintings that depict various scenes of cowboy life. The artist was Olaf Wieghorst, who appears in the film as the gunsmith, Swede Larsen.

El Dorado isn’t bad and it was again a box-office hit but to be brutally honest Wayne was looking his age a bit and isn’t very credible as the fastest gun in the West.

Rio Lobo

Writer Leigh Brackett had done Rio Bravo and had been obliged by Hawks and Wayne to plagiarize herself on El Dorado. Now the poor woman was made to do it yet again in 1970 with Rio Lobo. Hawks said, “When you find out a thing that goes pretty well, you might as well do it again.”

.

.

You might as well do it again

Robert Mitchum turned it down. After reading the script, he said it was “an even bigger piece of crap than El Dorado.” I fear he was right. Hawks himself was honest about it. “I didn’t think it was

any good,” he said. A perceptive man, Hawks. Never mind. It does have saving graces. There’s a lively sub-Rio Bravo shoot-out at the end. There’s some nice William Clothier photography of Mexico and Old Tucson locations, and quite a stirring Jerry Goldsmith score (and lovely guitar music over the titles). And there’s a good performance by cranky old Jack Elam with his shotgun, doing his Walter Brennan act (actually, he was a decade younger than Wayne).

It wasn’t a glorious end to the Western career of Howard Hawks but we should remember him for Rio Bravo, The Big Sky and, in particular, for Red River.

Perhaps because Hawks was so versatile, he didn’t become a ‘Western director’ in the way that, say, John Ford did. But Western lovers will watch a Hawks film with enjoyment, and they will get not art, necessarily (many of them don’t want that anyway) but straight-down-the-line, well-made entertainment. He famously said, “I’m a storyteller–that’s the chief function of a director. And they’re moving pictures, let’s make ’em move!”

.

.

Hawks (left) was perhaps the greatest Hollywood director never to win a Best Director Oscar (though he was given a consolatory honorary award in 1975 – by John Wayne). His friend and admirer John Ford generously suggested that he should have been recognized as best director, instead of Ford, for Sergeant York in 1941. Sergeant York was a fine film but it was perhaps Hawks’s bad luck that it came out the same year as Ford’s magnificent The Grapes of Wrath. For me, though, Hawks should have been a contender for Best Director for his 1948 picture Red River, a splendid film and one of the finest Westerns ever made. He wasn’t even nominated (Elia Kazan won it for Gentleman’s Agreement).

Hawks (left) was perhaps the greatest Hollywood director never to win a Best Director Oscar (though he was given a consolatory honorary award in 1975 – by John Wayne). His friend and admirer John Ford generously suggested that he should have been recognized as best director, instead of Ford, for Sergeant York in 1941. Sergeant York was a fine film but it was perhaps Hawks’s bad luck that it came out the same year as Ford’s magnificent The Grapes of Wrath. For me, though, Hawks should have been a contender for Best Director for his 1948 picture Red River, a splendid film and one of the finest Westerns ever made. He wasn’t even nominated (Elia Kazan won it for Gentleman’s Agreement).

2 Responses

Nice.

😉