An overwrought tear-jerker

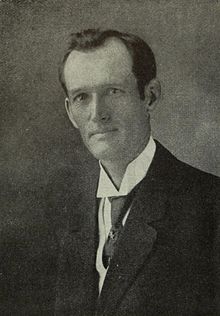

Henry Hathaway, pictured left, the temperamental director, had earlier helmed the same studio’s Technicolor picture The Trail of The Lonesome Pine (1936), with Fred MacMurray and Henry Fonda, which was also an “Adventure, Drama, Romance”, about feuding families in remote mountain districts. Now he wanted to have a go at the well-known story of The Shepherd of the Hills, with a similar plot. By 1941 this story was already, as Scott Eyman says in his biography of Wayne, “verging on the archaic.” The 1907 novel by Harold Bell Wright (1902 to 1944), a writer mostly forgotten or ignored after the middle of the 20th century but in his time a best-seller (he was the first to make $1m from writing fiction), was a rather saccharine Christian parable – Wright was a minister of the Protestant church known as the Disciples of Christ. Even the title has a Biblical ring.

Henry Hathaway, pictured left, the temperamental director, had earlier helmed the same studio’s Technicolor picture The Trail of The Lonesome Pine (1936), with Fred MacMurray and Henry Fonda, which was also an “Adventure, Drama, Romance”, about feuding families in remote mountain districts. Now he wanted to have a go at the well-known story of The Shepherd of the Hills, with a similar plot. By 1941 this story was already, as Scott Eyman says in his biography of Wayne, “verging on the archaic.” The 1907 novel by Harold Bell Wright (1902 to 1944), a writer mostly forgotten or ignored after the middle of the 20th century but in his time a best-seller (he was the first to make $1m from writing fiction), was a rather saccharine Christian parable – Wright was a minister of the Protestant church known as the Disciples of Christ. Even the title has a Biblical ring.

The book was twice made into a silent movie, in 1919, directed by Wright himself, and again in 1928. It would also be remade twice more after the Paramount/Hathaway one, in 1960 and 1964, so it was evidently a popular tale. I’m afraid the film versions were usually bucolic and romantic melodramas with great improbabilities of plot, but the 1941 one was saved by fine photography and good acting, even if the directing is surprisingly uneven (parts drag and parts are too wordy) and screenplay writers Grover Jones and Stuart Anthony struggled to make the story subtle, or even plausible – given the source novel, that was really an impossible task. Garfield calls it “an overwrought tear-jerker … a bit too soapy for some modern audiences”.

In The Shepherd of the Hills Duke, in his first color film, appeared with his boyhood hero, Harry Carey. I shall be writing at more length about Carey soon, so here suffice it to say that this was, surprisingly perhaps, the first time Carey and Wayne had worked together. Harry was a great influence on Duke, who had grown up watching Carey’s ‘Cheyenne Harry’ silent Westerns, often directed by John Ford.

Though Ford and Carey had fallen out in 1921 (Ford seemed to have this strange propensity for resenting those such as his brother Francis Ford and Carey who had contributed to his success) Ford nevertheless kept close to the Careys, especially Harry’s actress wife Olive and their son Dobe (Harry Carey Jr), and once Harry was safely deceased (he died in September 1947) Ford would sentimentally eulogize him by dedicating his 1948 picture 3 Godfathers (with Duke and Dobe in the cast) to Dobe’s father, “Bright Star of the early western sky”. In Shepherd Carey plays, as it turns out, Wayne’s dad, and indeed in many ways Carey was a surrogate father for Duke. It gave a piquancy to the climactic clash, missing in other versions.

Olive also told Wayne: “Harry Carey always wore a good hat, a good pair of boots, and what he wore in between didn’t matter too much.” Sound advice.

There was some awkwardness on the set because Wayne, then still married to Josephine Alicia Saenz, was pursued to the Big Bear Lake area by Marlene Dietrich, with whom he had started a passionate and pretty well unconcealed affair on the set of Duke’s previous picture, Universal’s comedy-romance Seven Sinners (and it would last at least until their shooting of The Spoilers together in ’42). Ward Bond phoned Olive Carey and told her Duke was missing in action, and cameras were ready to roll. Olive drove in the snow to where she knew Dietrich was, at nearby Arrowhead, and met Wayne walking along the road – his car had skidded on the ice and gone over an embankment. She drove him back to the set and normal service resumed, and though Hathaway, and probably everyone there, knew well where Duke had been, nothing was said.

Hathaway and his DP, the talented Charles Lang (some footage was shot by W Howard Greene), pulled off some remarkable Technicolor shots (the story is nominally set in Missouri but the California scenery is stunning). There are also memorable and beautiful interior shots, such as the one of simpleton son Pete (Marc Lawrence) catching dust motes in a ray of sun or Pete’s ‘Viking’ funeral in the cabin. Visually, this picture is very fine – and the modern print is excellent.

Ring of fire

Aside from Wayne and Carey, acting honors went to Beulah Bondi as the malevolent almost witchlike Aunt Mollie, undisputed leader of the Matthews clan. It’s a truly magnificent performance. Bondi was loved by directors and indeed she had been in both The Trail of Lonesome Pine, and with Carey (who was Oscar-nominated for his part) in Mr Smith Goes to Washington three years later. She herself was twice nominated for an Academy award and also later won an Emmy for her part in The Waltons. For me she was unforgettable in The Furies, Track of the Cat and The Baron of Arizona.

Other stand-out actors are Marc Lawrence and Ward Bond as Wayne’s brothers, and John Qualen and Fuzzy Knight as locals (Fuzzy gets a melancholic song), and if you don’t blink you’ll also spot Hank Bell’s mustache (with Hank attached) and Henry Brandon (the future Scar from The Searchers).

Less successful, I thought – though several reviews have been complimentary of her – was Betty Field as fey barefoot country girl Sammy, Wayne’s intended. She had been Mae, the farm girl, in Of Mice and Men in 1939 and so was probably thought to be good casting. But she comes across as a rather silly juvenile, one for whom hunky Duke would be very unlikely to fall. As a person Field was quite reserved and she tended to shun the Hollywood scene; in fact she deliberately didn’t renew her contract with Paramount when it expired.

The Hayes Office was “shocked and appalled” by the scene in which she removes her shirt and displays her bare back to the camera. Hathaway assured the Office that it was actually a man doubling for Betty Field during that particular moment. Phew, so that’s alright then. Field and Wayne, corroborated this. Years later, however, Field revealed that it was indeed her own bare back that was shown. How daring.

The feuding families at the heart of the story, far too finely laundered and well-spoken though they are, are supposed to be Ozark hillbillies of some unspecified time in the past, with limited intelligence, less education and riddled with seriously dumb superstition. It’s hard to relate to them in any sympathetic way. Wayne plays Young Matt, a wholesome, tall, strapping all-American man. He is out of place and his character jars. We do not believe that he would have a lifelong mission to kill his father, and his abandonment of the task in the very last reel and conversion to Careyite saintliness is equally unconvincing.

When Harry Carey comes to the community he is saintly to an absurd degree, digging a bullet out of Sammy’s pa’s shoulder, miraculously healing a little girl, giving work to the unemployable, showering money on the settlement, and generally dispensing wisdom, kindness and benevolence. The New York Times reviewer wrote that “Never … has there lived a man whose mere presence was so benedictive, whose utterances were more suitable for framing as wall samplers, or who wore his halo more rigidly fixed”. Carey’s performance is sober and authoritative but his character is one-dimensional and daft.

Missouri it ain’t but it’s mighty pretty

The scene in which Young Matt, after learning that Carey is his father, takes his rifle and walks to Carey’s cabin to shoot him, is well done, in long shot, and in fact I reckon that it must have made an impression on Howard Hawks, who reprised elements of it for the walk-down at the end of Red River when Wayne strides towards Montgomery Clift for the final clash.

The reviews were largely negative. The New York Times critic in particular slammed the picture, calling it “a brimming portion of sentimental mush” and adding “what must have seemed like potent drama in 1907 has become gummy emotionalism in 1941”. The film was a “too obvious an attack on the tear-ducts”. The review concluded by calling the picture “a lachrymose bore”. Myself, I wouldn’t go so far, though I do think the reviewer had a point. I may have been overgenerous in the revolver-rating but it was a Wayne/Hathaway picture after all, the photograhy is superb, and it’s a nostalgia/thank-you vote for Harry Carey.

4 Responses

I loved this movie…but it looks like I'm in the minority. 🙂

You have the perfect right to, Bev!

Call me a sap or whatever you want, but I worship at the altar of Henry Hathaway largely because of this film. I find it beautiful – sometimes stunningly so – both to look at and in its sentiments. It’s extremely well made with amazing attention to detail. The art direction/set design is exemplary with cabins and homesteads appearing like they have been lived in for years. Carey, Bondi, Lawrence and many of the character actor cast give their best work, which is another credt to the director. I think the picture is hugely underrated. By the way Jeff, that’s just a terrific photo of Carey and the Duke together.

You are not alone (see above, Bev, for example). I’m certainly not going to call you a sap!!