He made some pretty good oaters

Film titles with live links will take you to our reviews of those pictures.

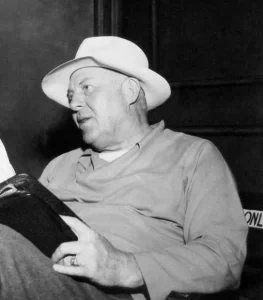

Nat Holt deserves our attention because though he produced films in other genres, being known for the likes of Riff Raff, Hurricane Smith and Flight to Tangier, he did in fact specialize in the Western, so may glory, laud and honor be his. Better yet, he made several pictures with Randolph Scott.

Born in California in 1893, he was, according to the New York Times, first a poster artist and stage manager. He started on contract at RKO and his first picture, as co-producer with Jack J Gross (who did all the RKO pictures with him) was a 1945 musical comedy.

Three Westerns with Randy

But soon thereafter came his first Randolph Scott Western, Badman’s Territory, directed by Tim Whelan (Whelan would helm three oaters for Holt), which RKO released in May 1946.

The picture was hardly one of the best Randy Westerns. The New York Times was quite generous when it called it “a lumbering action melodrama” and added that “Westerns seem to have a lot more life when told rapidly and concisely.” The day after, the Times’s sister organ The New York Daily News commented, “The quantity of events is not marked by the quality; in most of the conflicts the participants are too obviously a group of actors going rather awkwardly through the paces of a motion-picture scene.”

It has a totally preposterous plot and rather too much plot at that. In 1944 and ’45 Universal had had hits by grouping as many horror characters as you could think of in movies like House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula, in which Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, wolf men, hunchbacks and mad doctors crowded the cast list, and RKO must have thought they would have a go at that with outlaws. They would put the James gang, the Daltons, Sam Bass and Belle Starr all in the same movie.

Despite the reviews, though, it was a box-office success. The public loved it. Mind, Hollywood is still pulling that trick, with cartoon superheroes jostling cheek by, er, jowl in blockbusters of unending direness. Anyway, it was a good start for Nat.

The following year, Trail Street had Randy himself producing alongside Holt and Gross, a Bat Masterson yarn with Scott as Bat, of course, based on the novel Golden Horizon by William Corcoran. However, Randy doesn’t appear till a good quarter of an hour into the movie and you do get the feeling that Trail Street was something of a trail for RKO’s young star Robert Ryan, much as Columbia’s The Desperadoes (in which Scott also theoretically topped the bill) was for Glenn Ford. Randy was a modest and generous man, though, who was perfectly willing to stand back a little and give a good dose of the limelight to other actors.

Undemanding perhaps (The New York Times said it was “just another pistol drama”) it was all in all a very satisfactory Western with considerable oomph.

And in 1948 much of the cast and crew reassembled for a sequel to Badman’s Territory, titled Return of the Bad Men. This was orthographically interesting, for the one word badman had now been rendered in the plural as two, bad men. Who knows why? Of course a Western badman is rather different from a bad man. The former usually has saving graces, a semi-hero in fact, and is redeemed by the love of a good woman. Anyway.

Often, sequels aren’t as good as the originals but this one was better. In fact it was a whoop-de-woo Randolph Scott Western. Maybe it was the director, for this one was not helmed by Whelan but by Trail Street’s director, good old Ray Enright, who certainly knew a thing or two about the Western movie. This one stuffed in even more baddies than the previous effort, in fact they assemble the baddest gang of badmen you could ever wish for. Bill Doolin (Robert Armstrong) is the boss and in the ranks there are three Dalton brothers (Walter Reed, Michael Harvey and Lex Barker), three Younger brothers (Robert Bray, Tom Keene, Steve Brodie), Billy the Kid (Dean White) and the Sundance Kid (Robert Ryan, again, splendid this time), among others. And against all those, one lawman, Marshal Vance (Scott). Great stuff.

Farewell RKO – more Randy though

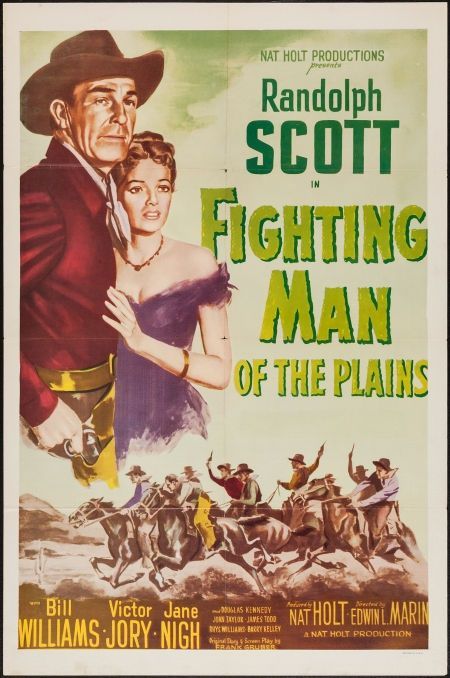

The New York Times of April 6, 1948 reported that Holt was leaving RKO and had set up a deal with 20th Century Fox to make three pictures, costing $2.5m each (big bucks in those days). They were to be The Cariboo Trail, Fighting Man of the Plains and Canadian Pacific, all Westerns starring Randolph Scott.

The first and third were Canadian stories, with scenes shot in Alberta and British Columbia, particularly the Banff National Park, though they were straight Westerns in other respects. Cariboo was about gold discovered in British Columbia and how Randy and his partners drive cattle up there from Montana to settle in the Chilcotin country, “a cattleman’s paradise”. In fact, though, it could have been set anywhere and is a pretty generic Western, with standard elements such as a town owned by the bad guy, rustlers stampeding the herd and the like. Variety called it “a scenic outdoor action feature that shapes up well” which just about sums it up.

Canadian Pacific, one of those Union Pacificky nation-building railroad pictures, with Scott as a two-gun surveyor, was certainly not one of Randy’s better Westerns. In fact it was one of his weakest. In his good book The Films of Randolph Scott (McFarland & Company, 2004) Robert Nott is particularly down on it and goes so far as to call it “abysmal”. Nott says, “It may not be Scott’s overall worst film, but I rate it as his overall worst Western.” He adds, “Randolph Scott or no Randolph Scott, it stinks.” Myself, I think that’s going a bit far. It does have action, color, and Victor Jory as villain, after all (Jory was the bad guy in Cariboo too). But I do admit, it’s pretty weak generally.

Both were directed by Edwin L Marin, a Holt/Scott favorite, and both were shot by cinematographer Fred Jackman Jr. Cariboo was written by Jack de Witt and Kenneth Gamet.

While Canadian Pacific had a screenplay by Frank Gruber and Randy’s pal John Rhodes Sturdy (a splendid British Empire name if ever there was one).

To be blunt (and your Jeff does blunt) these pictures were pretty low on the Scott Oater Scale (SOS). Coroner Creek the year before and The Nevadan the year after were vastly superior. Oh well.

The Holt/Scott oater between the two Canadian ones was very much better. It was also written by pulpmeister Frank Gruber and directed by Marin but it had a good deal more zip and pzazz. Film historian David Quinlan wrote, rather harshly perhaps, that Marin “never managed to make a memorable film” but Quinlan did add, “But he had a sure visual eye that often produced pleasing results, notably in some of the Scott Westerns.”

The opening sequences are actually quite surprising. Scott shoots down an unarmed man. You see, during the attack on Lawrence, Kansas, guerrilla leader Quantrill, played by James Griffith and as so often billed as Quantrell, tells Randy that the man was the one who killed his brother. Still, this isn’t what we expect from Randy. What’s more, it turns out the man was innocent. Oops. Randy fetches up in the (fictional) town of Lanyard, Kansas where the crooked town boss is Slocum (Barry Kelley), the real assassin of Randy’s brother. Coincidence, huh? There are other amazing coincidences and stretches to credibility, such as when Joan Taylor as Evelyn, the daughter of the man Randy shot in Lawrence, happens to live in the town and doesn’t recognize him. In fact she falls for him. But then stretches of credibility are part of the joy in Westerns, n’est-ce pas?

A curious feature of the movie is the big build-up given to a virtual unknown, the 26-year-old Dale Robertson, in the part of Jesse James. He only appears twice, first 55 minutes in, and for very short times, and it was Robertson’s (credited) screen debut and first Western.

The picture played well, despite the extremely iffy plot. The Los Angeles Times said, “Fans that hanker to see first rate ridin’ and shootin’ will go for Fighting Man of the Plains.” And The New York Times opined, “Judging by the eager-eyed audience yesterday at the Rialto … thundering hooves and barking six-shooters can still fill a theater when all else fails.” The reviewer added that when Jesse James saved Randy in the last reel, “The general yell that hit the Rialto ceiling was enough to make the original outlaw sit up in his grave and take a bow.”

O’Brien and Paramount

Now it was Paramount. In 1951 Holt produced three Westerns, two of them with another actor he liked, Edmond O’Brien (The LA Times in February ’51 reported that Howard Duff was to star but fortunately that didn’t happen), but before that Paramount released The Great Missouri Raid, a Frank and Jesse James yarn with Wendell Corey as Frank and Macdonald Carey as Jesse – Corey ‘n’ Carey, I call them. And if you mix up your Coreys ‘n’ Careys a bit, you’re not alone. Holt admitted to them later that he had got confused, and had meant to cast Wendell as Jesse. Awkward. Carey recalled that they were often mistaken for each other. They had quite a lot in common; they were about the same age, they lived on the same street, they were both alcoholics.

The supporting cast was pretty good, and included Ward Bond as the chief villain, bringing some weight to the role, with James Millican as his equally villainous brother. Bruce Bennett, Bill Williams and Paul Lees are the Younger brothers. Paul Fix and Ray Teal are Union army sergeants. Frank Ferguson is a townsman, James Griffith is a sneaky spy, and Whit Bissell is a weasel-like Bob Ford. Not bad.

Director Gordon Douglas had a mixed record, as he himself cheerfully admitted. He churned out bread-and-butter pictures for a living, not all great by any means, but every now and then he put together a really nice Western. Myself, I especially like Fort Dobbs, The Nevadan and The Fiend Who Walked the West. However, I’d put The Great Missouri Raid more in his bread-and-butter class, to be honest, though it gallops right along. Douglas was good at action, and there’s plenty of it. Yak Canutt was stuntmeister. The James gang blow up banks, rob trains, gallop about and such.

The pressbook for the movie puffed it as historical. “After painstaking research involving little known records, correspondence and newspaper accounts, producer Holt has placed before his camera the authentic history of America’s most sought-after outlaws.” It added, “To set matters right, top historical novelist Frank Gruber performed extensive research before he committed the screenplay to paper. The result is a startling historical revelation, as well as spine-tingling proof that truth is more stirring than fiction.” Please place your belief in that in the receptacle provided (spittoon).

At the time The New York Times praised it, moderately: “Frank Gruber’s story and screen play give the outlaws decent lines to speak and loads of opportunities for hard riding, fast shooting, and a modicum of romance for the Jameses.” Variety said, “Gordon Douglas’ direction swings the footage through many exciting moments. The bank holdups that follow the personally-inspired raids against the Jameses, the train robberies, the flights through rugged terrain, the more intimate family and romance incidents are all told most acceptably.” So they liked it. Brian Garfield called it “not very fresh”. He had a point.

All in all it’s quite a fun watch and certainly a lot better than most of the black & white low-budget Jesses of the era. It’s well directed and photographed, and with better leads might actually have been quite good.

The two O’Brien oaters were Warpath and Silver City. They were both written by Gruber (Silver City from a Luke Short novel), both photographed by Ray Rennahan, who shot nine pictures for Holt, both had Paul Sawtell music and both were directed by Byron Haskin, a newspaper cartoonist become cinematographer and special effects man (he’d worked at Warners on Errol Flynn Westerns) who would direct The First Texan with Joel McCrea and become resident director on the TV show The Californians. He worked quite a lot with Holt.

Warpath co-starred Dean Jagger, Forrest Tucker and Harry Carey Jr, so that was good. It was a rather typical Custer story in the sense that like most movies that featured the general, it was a tale of someone else, with Custer himself (John Millican) as an ancillary figure who appears now and then. A good deal of the plot bears a remarkable resemblance to that of Ernest Haycox’s novel Bugles in the Afternoon (made into a movie itself the year after Warpath). I’m not saying that screenwriter Frank Gruber plagiarized it or anything but it is certainly true that both concern a former Army officer who in 1876 enlists as a trooper in the 7th Cavalry for personal reasons, fights a bullying sergeant played by Forrest Tucker, is made a sergeant himself, saves the day for the cavalry with his heroics and ultimately gets the girl. Coincidence, huh.

The New York Times was a bit snooty about it. “Mr. Holt makes no bones about art and occasionally one of his shiny rootin’-tooters is mildly diverting, on its own level. At any rate, the Globe’s little picture is a reasonably digestable [sic] sample from the Holt feedbag.” I reckon it’s a nice little oater, though, if we are talking of feedbags, and it nips right along.

Silver City co-starred Yvonne De Carlo, replacing first-mooted Rhonda Fleming, and Richard Arlen. Ms De Carlo did some dreadful tripe as far as Westerns go, stuff like Salome Where She Danced and Calamity Jane and Sam Bass, but she is really good in this one, and she’d work for Holt again. In its review, the Los Angeles Times said the storyline was occasionally “baffling” but the film was full of “heaps of novel and exciting incidents”. Myself, I didn’t find the plot baffling at all, but then I had read the book.

The picture made $1m. Holt productions rarely lost money, though this one hardly shone commercially (that year MGM’s Across the Wide Missouri made $5.5m and Westerns like Universal’s Cattle Drive, Warners’ Distant Drums and Columbia’s Man in the Saddle all did better).

Brian Garfield in his 1980s guide dismissed it with the one word “ordinary” but I think it’s better than that. I agree it’s not as good as some Westerns that year, in particular the fine Westward the Women; it’s a nevertheless tight little oater, well done. I consider it an enjoyable action Western, with strong characters, a good (if fairly traditional) plot, well written, directed and acted.

Holt and O’Brien teamed up again the following year in one of my all-time favorite Westerns, the absolutely excellent Denver and Rio Grande. There were pretty well the same guys behind the camera, Haskin, Rennahan, Gruber & Co, and quite a few of the regulars in front of the camera too, O’Brien, Jagger, J Carrol Naish et al, with the addition this time of Sterling Hayden as the bad guy, aided by star badman Lyle Bettger. The whole thing was huge fun and really what a 50s Western ought to be. I saw it when I was a small boy (Bronze Age) and have never stopped admiring it. What really struck me as a lad and still does is the utterly spectacular crash, with two locomotives smashing at full speed into each other on the single track. The picture was filmed on the Durango to Silverton railroad, which I love.

The same year, still at Paramount, Hayden, and Tucker and Jory were back in Holt’s Flaming Feather, a curiously old-fashioned Western in many ways, directed by Ray Enright, written by Gruber – this time with Gerald Drayson Adams. Rennahan and Sawtell were back too. Aside from the Technicolor it could have been made at any time in the 1930s with any number of programmer/serial cowboys in the lead. The plot is the old one about a mysterious bandit who is marauding through Arizona, but is eventually unmasked by the hero and turns out to be the leading townsman. I thought it was great.

You’d have to say that so far, these Nat Holt oaters may not have been great art but they were ‘proper Westerns’, and many of them darn good.

Two duds

1953, though, was the year of two which (IMHO) weren’t. Some people like Arrowhead and Pony Express, and some people like their star, Charlton Heston. I am not among them. I find Arrowhead plain noxious and Pony Express downright daft. And I thought Heston was only ever good in one Western in his whole career (Will Penny). But there we are. It’s all down to taste, I guess.

Arrowhead was directed (and written) by Charles Marquis Warren and Pony, also written by Warren, was helmed by Jerry Hopper. Neither got it right. For one thing, they grossly underused some fine actors – Katy Jurado, Brian Keith, Jack Palance, Forrest Tucker (completely overshadowed as a nonentity Wild Bill Hickok), all wasted.

The pictures also claim to be historically accurate. I have no objection to unhistorical Western movies. They are not supposed to be documentaries but entertainments. But when they claim to be historical and are clearly preposterous, then they lay themselves open to criticism.

Reviews were far from favorable, though. The New York Times said of Arrowhead, “It is neither a pretty nor a captivating film. Mr. Heston makes an unappealing hero and Jack Palance makes a dour Apache brave. Katy Jurado is slinky and sultry as an Apache fifth column at the cavalry post and Brian Keith is conventionally rakish as the captain of the cavalry troop. The scenery is occasionally pretty. That’s about all that can be said.” More modern reviews have not been kinder. In Pony Express there is a great deal of plot and thus a lot of talking, death for a Western – The New York Times reviewer said, “The picture threatens to become an arch conversation piece”. Brian Garfield said that Holt was aiming to make a large-scale DeMille-style picture “but the result is a juvenile B-movie gone rampant.” He added that “both stars overact” and “some of the dialogue is funny but it’s hard to tell whether that was intentional.” Dennis Schwartz said of it, “The 101 minutes is not justified to tell this modest story. Also the directing by Jerry Hopper lacks imagination and he fails to give the film an overall shape.” Too right.

Oh well, as I say, some people like these movies. That’s fine.

Better

There would be three more big-screen Westerns from Holt.

The first, with Nat’s son Nat Holt Jr as assistant, was back at RKO, in March 1955, and back with Randy, and it was a lot of fun – way superior to those ’53 pictures. It was Rage at Dawn, a Reno brothers yarn – though of course when a Western movie starts with the words on screen “This is the true story of…” you know it’s going to be complete bunk historically, and you are not disappointed (or are if you believed it). It was written once more by that esteemed historian Frank Gruber, with Horace McCoy.

Randy is working under cover for the “Peterson” detective agency (Westerns often thinly disguised the name, perhaps because the Pinkertons were still active and they feared legal suits). He says he’s 35 in the script, which is a bit rich (he was 56). He inveigles his way into the gang, cunningly trapping them. He has enough time, however, to romance the Renos’ (very posh) sister Laura (Mala Powers).

It was another Whelan-directed picture. It has some good action scenes. The outlaw Reno bros are Forrest Tucker, J Carrol Naish, Myron Healey and Richard Garland. Denver Pyle is ‘Honest Clint’, the brother who kept to the straight and narrow. But the best acting came from the rascally trio of judge, prosecuting attorney and sheriff in the ample shape of Edgar Buchanan, Howard Petrie and Ray Teal, respectively. What an excellent combination!

Six months later came the release, also by RKO, of a different Western, Texas Lady, starring Claudette Colbert. Whelan was at the helm once more (it was his last film) and this time Horace was at the typewriter without his sidekick Gruber. There were some nice Columbia State Historic Park locations shot in ‘SuperScope’ and Technicolor (Ray Rennahan again).

The famous Hollywood actress Claudette Colbert, one of the top celebs of her time, who in the 1930s had starred in comedy-romances such as It Happened One Night (for which she won an Oscar) and Midnight, didn’t do Westerns. They weren’t her thing. She was cast for John Ford in the eighteenth-century drama Drums along the Mohawk in 1939, if you call that a Western. In fact she got top billing in it, but she was unconvincing as Henry Fonda’s frontier wife and her acting was very old-fashioned. Colbert also returned as co-star to Clark Gable (the male lead in It Happened One Night) in Boom Town in 1940, a drama romance about wildcatters (Gable and Spencer Tracy) becoming oil tycoons and loving the same woman (la Colbert) but I wouldn’t call that a Western either. No, in reality, Texas Lady was the only true Western she made. Perhaps she thought the genre beneath her, I don’t know. But in any case she wasn’t terribly suited to it.

She plays a lady gambler who pays off her dead daddy’s debts with the cash she has gained by cleaning Barry Sullivan out on a riverboat and then sets off for darkest Texas where she intends to take charge of the only asset her late pa left her, a small-town newspaper, The Fort Ralston Clarion. The local ruthless rancher types will have no truck with a woman (a woman, indeed!) running a paper and maybe criticizing them for being overbearing. She gradually manages to win over the townsfolk to her side, aided by a broken-down alcoholic lawyer whom she reforms and who acts for her (James Bell) and the saloon owner, who is, unusually for Westerns, a goody (our chum John Litel), and, especially, by gambler Barry, because he turns up again too. Barry defeats the ranchers’ hired gunslinger, wounding him and sending him off with his tail between his legs, with a derringer, one of those sleeve types that you can dash into you palm because it’s on a spring. Well, that certainly sent the film up in my estimation.

To be brutally frank, Texas Lady was not the best Western to come out in the mid-1950s. The late Brian Garfield summed it up pithily as “Predictable, rambling, slow.” And I think Ms Colbert was probably right to eschew the genre. Poster slogans like WOMANLY WILES WERE HER WEAPONS! and A LADY TILL THE FIGHTING STARTED, THEN WHAT A WOMAN! sound a bit outdated these days. Still, it does have its plus points here and there.

TV

After Texas Lady, with the market for theatrical Westerns faltering, Nat turned to TV. A Tale of Wells Fargo, which aired on CBS as part of the Schlitz Playhouse of Stars in December 1956, was the pilot for NBC’s very popular Tales of Wells Fargo, with Dale Robertson, which ran for an impressive six seasons 1957 – 62. For its first two years, the series was in the top ten of the Nielsen Ratings. During the 1957–58 season, it was ranked number three, and during the 1958–59 season, it was ranked number seven.

It was supposed to be based on the life of Wells, Fargo detective Fred Dodge, though of course Robertson’s Jim Hardie was fictional. All sorts of famous Wild West characters appeared (rather like Stories of the Century) and every Western character actor you care to name appeared too. It was great for that. I loved this show back then and was a huge admirer of Dale. Whenever he appeared in a Western movie he was still always Jim Hardie for me, moonlighting.

Holt old-faithful Frank Gruber was co-creator and penned many of the teleplays, though a lot of other writers were used, even Louis L’Amour for four episodes. After three seasons, Earle Lyon took over as producer.

While Wells Fargo was still riding high another Holt-Gruber show hit the airwaves, Shotgun Slade. It didn’t enjoy quite the success Wells Fargo did but it still ran for two seasons. Like Jim Hardie, Scott Brady’s Slade wasn’t an official lawman. You’d think Jim was head of the Secret Service at least the way he bossed local sheriffs and even US Marshals about and they meekly did his bidding, even though he was an employee of a private company, and Slade too was a private detective, not a sheriff or marshal. PIs were rather the thing then. And the modern jazzy music rather than traditional ‘Western’ score enhanced the TV private eye impression.

The gimmick-gun was also all the rage at the time, what with Steve McQueen’s Mare’s Leg, Lucas McCain’s trick rifle, Johnny Ringo’s LeMat, with its shotgun barrel under the pistol one, and so on. Slade’s weapon of choice had a lower barrel which fired a 12-gauge shotgun shell, while the top barrel fired a .32 caliber rifle bullet. Snazzy.

Holt also produced the show The Tall Man (to be reviewed in May on Jeff Arnold’s West, you will be ecstatic to learn), the Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid series created by Samuel A Peeples with Barry Sullivan as Garrett and Clu Galager as Billy. It also ran for two seasons, 1960 – 62.

And in 1960 Holt launched Overland Trail. I wasn’t so keen on that one (I never liked William Bendix) though my sisters sighed over Doug McClure, I recall. Anyway, it was axed after seventeen episodes. Still, Nat was kept pretty busy.

One last big-screen oater

With Wells Fargo, Shotgun Slade, The Tall Man and Overland Trail all pulled, Nat Holt had one last Western hurrah when he returned to the big screen with the July 1963 release of MGM’s Cattle King. It’s an early 60s Western, yes, but in many respects it’s a 1950s one: it’s played straight in the classic tradition. The lead role could have been taken by James Stewart, Gregory Peck, Henry Fonda or a number of other Western leads of that time. But Robert Taylor does it really well, bringing the right degree of Western grit and decency to the part.

The MetroColor is bright and the picture quality on my DVD good. There are some nice (Californian) location shots (DP William E Snyder, of The Man from Colorado fame). There’s good Paul Sawtell music. The movie was written by Thomas Thompson, also credited as an associate producer (his only film as such). Thompson was a TV writer (especially of Bonanza and Temple Houston) and only wrote two feature Westerns – the other was the screenplay for another Robert Taylor Western, Saddle the Wind, in 1958. The script for Cattle King isn’t bad, in fact.

The ensemble was directed by Tay Garnett, probably most famous for A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and the 1946 version of The Postman Always Rings Twice, but not really known for Westerns – in fact I think Cattle King was the only big-screen Western he did. He does a fair job, it must be said, and the picture moves along at a brisk trot, with some good action scenes – the final showdown is well handled.

I quite like this film. It’s no great Western, and it’s certainly not Robert Taylor’s finest, but it rattles right along in a 50s sort of way and is enjoyable.

Like all Nat Holt Western movies, this one did not stint on location shooting; there was quite limited soundstage work. That was the result of the budget Holt was ready to assign to his pictures, and the cinematographers he hired made good use of them as a general rule.

And that, dear readers, as far as Nat Holt’s Western career was concerned, was that. I reckon he deserves a spot in the Jeff Arnold’s West Hall of Fame.

3 Responses

Jeff, this is one of the best pieces you have written. I salute you. Now, a few personal observations regarding Nat Holt.

My cousin and I saw Trail Street at a major New York City venue. In those days ushers were in uniform and for this picture, western outfits. Most enjoyable. The other Nat Hlt Scott films made back-to-back-to-back, Canadian Pacific, Fighting Man of The Plains, and Cariboo Trail, were all successful. no one gives a rat’s ass about The NY Times, put Randy inthe top ten box office attractions, and that went on for four years. A big deal.

Nat Holt’s later films, whether his fault or no one’s, Rage at Dawn and Texas Lady were bombs. Texas Lay was just lousy, and under-written. Claudette Colbert should have known better, and if you want to see her at peak performance, take a gander at Since You Went Away. Barry Sullivan was fine, but at this time, he was propping up older ladies, a formidable task. Colbert was done, but a great star nevertheless. As for RAge at Dawn, i always thought Tim Whelan’s work was a significant problem. I still believe that.

Thank you, Barry, very kind.

I just love the idea of the ushers in cowboy duds!

And I agree, many’s the Western slammed by the critics (especially the NYT: Bosley Crowther always seemed down on the genre) which nevertheless was a big hit at the box-office. The ticket-buying public and ‘cinema’ writers were often at odds as to what was good.

Good article, thank you